Caution on copyright should you wish to use photographs and diagrams from my website. I have included attribution wherever known and attempted to seek permissions from authors/owners of copyright who could be still found. This was not possible in all cases as the source of the photo was unknown or no longer in existence.

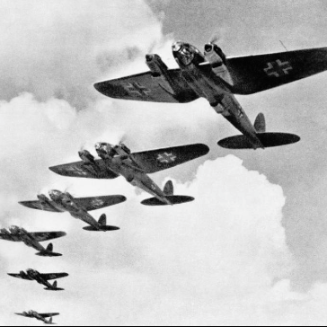

My first acquaintance with aircraft was as a very young child. Born 5 months before the outbreak of World War II and our house being less than 15 miles east of the centre of London, we lived under the flight path of German bombers attacking the capital. I was too young to remember all the windows of our house being blown out by an aerial mine but I do recall lying at night next to my mother in our lounge under the Government supplied Morrison air-raid shelter, a steel table, listening to the unmistakable noise of German bombers droning overhead. Perhaps my very first recollection of being alive was the day my mother took me to the small shed in the park at the rear of our house. This shed was the distribution point for gas masks. The man there, aided by my mother, tried to get me to put on a child’s mask, known as a Mickey Mouse mask, like the one shown below. This object, and the even more frightening adult mask, absolutely terrified me and I began screaming. I still recall me screaming and such was my protest that they gave up and I never wore the awful thing!

ANDERSON AIR RAID SHELTER – called a dugout. I spent one night in one of these at my aunt’s in Enfield, North London. It was very cramped with 4 adults and 3 children. Being so much closer to the centre of London, I could hear the frequent “crash” or “crump” noise of bombs but being so young, I was not especially frightened.

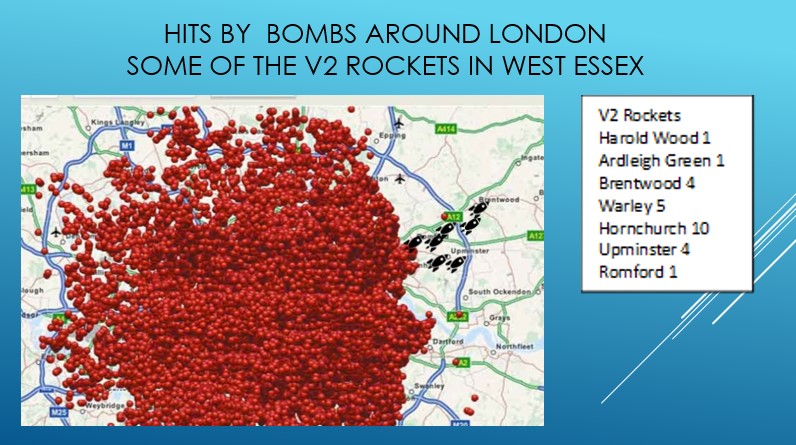

My father had survived the horrors of World War I in the trenches and had become a sergeant in the 1st London Rifles in charge of a Lewis machine gun team. During WW2 he worked in a factory but at night he was a member of the Home Guard. I entered our front room one day to find a Lewis machine gun there – an enormous gun to my child’s eyes! One day, in the later stages of the War, my friend and I were in the park to the rear of our house when we saw a V1 flying bomb – a doodlebug as it was colloquially known – flying overhead – making its unique sound due to its pulse jet engine. We watched it disappear into the distance. The V1 was the first of Hitler’s terror weapons – V for Vengeance! Although our fighter aircraft could and did shoot them down, it was a dangerous practice as the explosion could damage , even destroy the fighter. It was then discovered that flying in very close formation, the fighter pilot could position his wingtip just under the wing of the V1 with the result that the V1 would roll over and crash. Later we had the V2 – an intercontinental missile from which there was no defence since its flight time from the mainland coast of Europe was only 4 minutes. Fortunately, the third Vengeance weapon, the V3, was destroyed in its infancy by Allied bombers! Ardleigh Green school, a mile and a half from ours, was flattened by a V1 and the children had a short holiday. Our school, the Harold Wood County Primary, survived with only the tiniest of damage to the headmaster’s study and we did not get a holiday. Such is the unfairness of war! So my very early years were regularly punctuated with the awful wail of air raid sirens but we were never subject to the serious bombing experienced by the population a few miles further west.

V1 – FLYING BOMB – DOODLEBUG Height: 1.42 m (4 ft 8 in) Engine: Argus As 109-014 Pulsejet Guidance system: Gyrocompass based autopilot Operational range: 250 km (160 mi) Speed: 640 km/h (400 mph) flying between 600 and 900 m (2,000 and 3,000 ft)

V2 – BALLISTIC MISSILE – Operational range: 320 km (200 mi); Diameter: 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in); Speed: Maximum: 5,760 km/h (3,580 mph); At impact: 2,880 km/h (1,790 mph) Warhead: 1,000 kg (2,200 lb); Amatol (explosive weight: 910 kg)

The rocket icons show areas in west Essex hit by V2 rockets and the number of hits. Harold Wood is located up a little on the map from Upminster and in the centre of the rocket icons shown but only received one hit by a V2. I recall looking, with my friends, at the gutter of our headmaster’s study which had been broken off by a piece of falling debris.

My first love was steam railways, prevalent at the time of my childhood, a convenient interest since our house, 67 Recreation Avenue in Harold Wood in Essex, was less than a mile from the railway station on the four-track mainline to Liverpool Street. At the age of about three years I set off on my tiny tricycle and, successfully crossing what was then a main road, reached the station. Passing unseen below the gaze of the man in the ticket office, I dragged my tricycle down the stairs and onto the platform. There I savoured the experience of express trains passing at 60 miles an hour until my distraught mother arrived on the scene and my adventure was over! The epilogue to this love of steam trains came in July 2019 when my children gave me a special present for my 80th birthday – a steam locomotive driver’s experience on the North Norfolk Railway!

Living in Harold Wood we were not far from the RAF airfields of North Weald and Hornchurch. In the years following the end of the Second World War it became very common to see flights or whole squadrons of Vampire and Meteor aircraft flying overhead our home. I had not the faintest inkling then that one day I would be an officer in the Royal Air Force and piloting a Vampire.

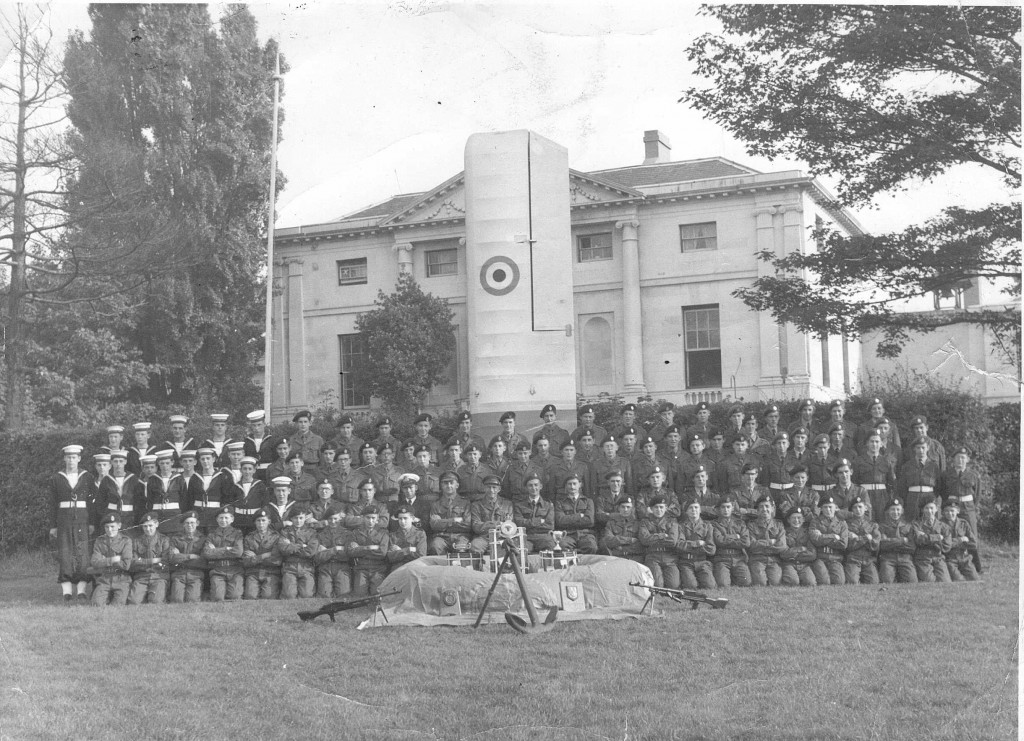

Interest in becoming a pilot began in the CCF (Combined Cadet Force) at the Royal Liberty Grammar School at Gidea Park in Essex. I rose to the rank of Flight Sergeant and gained a marksman badge for shooting – the Lee Enfield .303 rifle and the automatic Bren Gun – an interest that I have kept over the years. The award of a Flying Scholarship provided 30 hours flying training on Tiger Moths at the Herts & Essex Aero Club at Stapleford Tawney ending with the qualification of a PPL (Private Pilots Licence).

AIR EXPERIENCE IN AN AVRO ANSON (photo taken by and appears by courtesy of Barry Kraushaar) Chris Hogg, Ray (Tubby) Achurch, Harry Carter, self and Roy Woolley

ROYAL LIBERTY GRAMMAR SCHOOL CCF The wing is part of the primary glider – unfortunately wrecked by the woodwork master, one of our officers, who managed to fly it into one of the two oak trees on the sports field!

The Tiger Moth is a classic biplane, an excellent training aircraft even if very cold in winter and not hot even in summer! The RAF supplied 3 pairs of flying gloves which could be worn simultaneously, one over the other, and beautiful thick sheepskin boots but a thin flying suit. The aircraft had no radio or intercom and communication between instructor and pupil was via Gosport tubes – rubber tubes one shouted down, ending in earpieces inside the leather helmet! The instructor sat in the front seat with the pupil in the rear. I had to wait until my 17th birthday to do my first solo flight. It was a great privilege to fly such an aircraft!

The PPL Course included a 160 miles solo cross country flight including two intermediate landings. So from our base at Stapleford Tawney in Essex I flew to Ramsgate airfield in Kent and then on to Lympne airfield where I would need to refuel and finally back to Stapleford Tawney. During my flying history I have experienced several frightening moments and one such occurred on the second sector of this triangle. I took-off from Ramsgate to discover that unforecast very low cloud covered the route. I didn’t know whether the cloud base would permit me to fly safely underneath so, rather foolishly, without thinking about the implications of an engine failure, I decided to fly across the cloud and pick up the coastline, then find Lympne. All went well until I reached the coast which was clear of cloud. I searched for Lympne airfield but I had hit the coast too far west. I found myself circling the town of Rye but was sure it was Lympne. But, of course, there was no airfield. The fuel gauge in the Tiger Moth is a small float in the top of the fuel tank which is sandwiched between the two upper wings. It can be sen in the photograph of G-AIDS. The fuel was getting lower and lower and at one point I was even considering landing in a field, which I felt would probably have ended in a crash! This was a classic situation into which aviators can fall – trying to make what can be seen fit what one wants or expects to see! Eventually, the penny dropped and I realised my mistake, dismissed Rye and headed for Lympne! I flew east and found Lympne and its airfield and landed. Phew! I fully expected air traffic control staff to enquire as to my late arrival but, of course, they had no idea of my timing! So after refuelling, I took-off again and returned to Stapleford Tawney without further incident.

I completed 6th form and applied to the RAF to become an officer and pilot. After attending the Aircrew Selection Centre at RAF Hornchurch I was informed that I had been rejected. I was devastated! My world had been destroyed. Depressed and despondent I reported to the Labour Exchange, the then equivalent of a Job Centre. The woman I spoke to read my educational qualifications and directed me to go and see my former headmaster. He was very sympathetic. He understood my unhappiness and said he would obtain a place for me on a degree course at the University of London WHERE I COULD JOIN THE UNIVERSITY AIR SQUADRON.

My life began again! I mention this episode just in case any of my readers ever feel that the World has closed in upon them….never feel despondent or accept defeat!

So there I was, enrolled for a B.Sc.Engineering (Aeronautical). I confess that this step was taken with the primary interest of flying with the University of London Air Squadron (ULAS) at weekends and during the summer holidays.

The university air squadrons were part of the RAFVR and was staffed by RAF officers who instructed on the Chipmunk aircraft. We had the rank of Cadet Pilots and the RAF actually paid us for our attendance at the headquarters building in South Kensington and when flying. Incidentally, our squadron HQ building in Princes Street was right next door to the Iranian Embassy where, some years later, the SAS would perform one of their most notable exploits! When I joined, the squadron was based at RAF Biggin Hill with Chipmunk aircraft. I still remember my first night. After checking in at the Officer’s Mess, I waited for an orderly to light the fire in my room. After he left I soaked in the occasion. There was I, a nobody from nowhere, occupying a room in which some of the greatest heroes of the Second World War had spent time. Some of these brave men would have left the room during the day and later a fellow officer would have entered to collect personal effects! I felt very humble but also exhilarated at my good fortune. In my opinion, only Bomber Command crews deserved higher praise, with the odds so stacked against them. The total number who joined Bomber Command was 120,000. Of every 100 airmen 45 were killed, 6 were seriously wounded, 8 became Prisoners of War, and only 41 escaped unscathed (at least physically)!

ULAS CHIPMUNK WITH SQUADRON MEMBERS – Martin Gottesman, Ron Howell, the author, Mike Gibson (later to become Air Marshal Gibson – chief executive of NATS)

My instructor was a certain Flight Lieutenant Roy Pearce. He had a keen sense of humour and referred to me as “the dreaded bloody Ashpole”! Flying with Roy was always a good experience and I learnt a great deal from him. After a few months the squadron was relocated to White Waltham to the west of London. During the Summer holidays we were relocated to RAF St Eval one year and RAF St Mawgan the next. These were fun times both flying and social. On another occasion we were paraded outside the Royal Albert Hall as a guard of honour to the Queen Mother.

After two years at university I had had enough of aeronautical engineering, taught as it was in a most boring fashion consisting of maths and more maths so, with 160 hours flying time on the Chipmunk, I decided to apply for a five year short service commission in the Royal Air Force. This time it was just a matter of asking my commanding officer who produced a form for me to complete – I had proved myself in ULAS so the RAF knew what they were getting, hence no need for me to attend the Aircrew Selection Centre again.

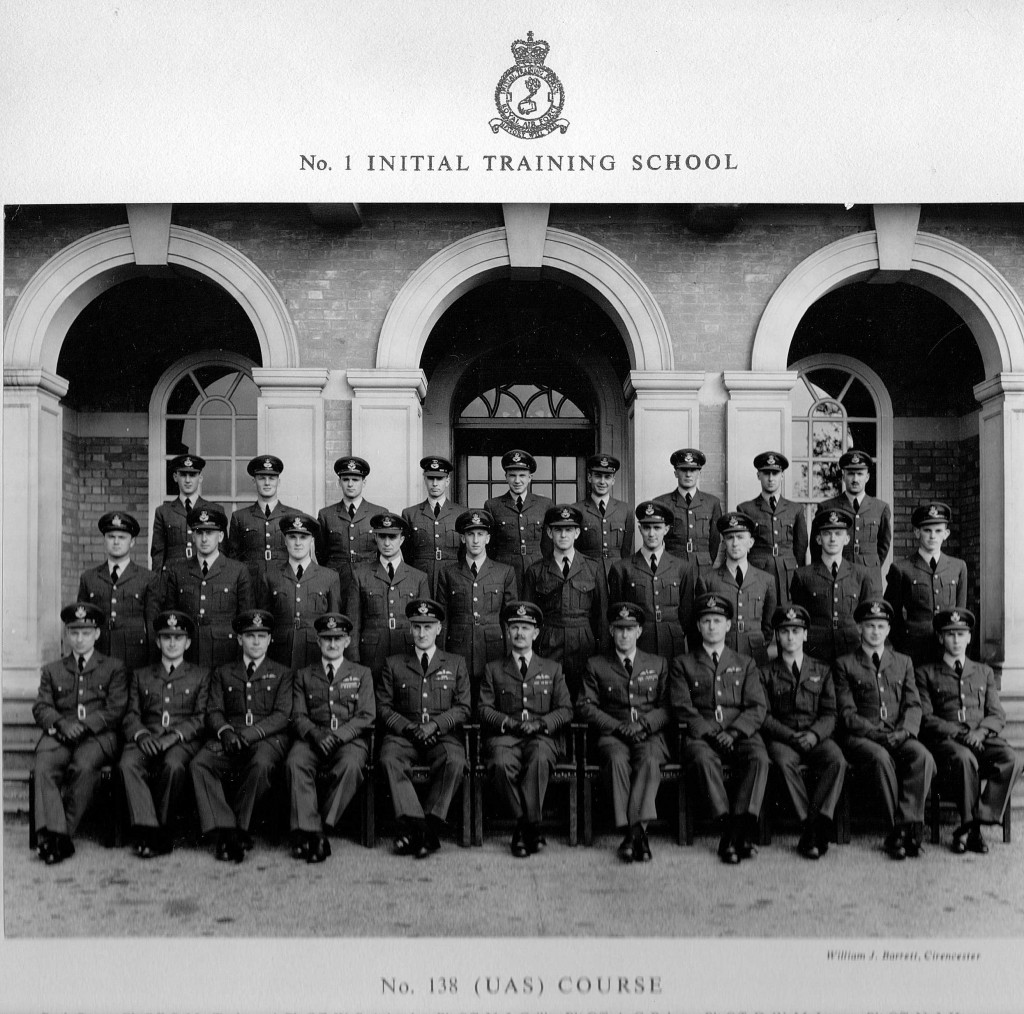

No. 138 University Air Squadron (UAS) course was composed entirely of entrants from the various universities around the country. Our first posting was to RAF South Cerney in Gloucestershire. Normally, potential pilot candidates would arrive as cadets then spend three months during which they would drill, exercise, be taught some basics about what was expected of an officer in the RAF, and so on. 138 UAS course was different. All arrived as pilot officers or acting pilot officers. We were all relatively known quantities so only one month instead of three was allotted for basic training.

In my opinion, one of the most important facets that are taught in all basic training camps is the realisation of one’s place in the scheme of things. By this I mean that anyone who is self-opinionated or thinks he is above the “system” will be taught the error of his ways. Our lesson in this came from two sources. The first was one evening a few days after our arrival. We were all assembled in the lounge of the officer’s mess and addressed by a squadron leader. He told us in an uncompromising speech that we had given the impression that we thought ourselves as rather “special”. He mentioned, in particular, the state of cleanliness of our rooms. His displeasure was evident. He concluded by stating that unless we demonstrated considerable improvement to the satisfaction of our superiors, we would not be permitted to touch another RAF aircraft. This address had a remarkable effect and that evening the sounds of vigorous scrubbing and dusting could be heard all around the mess! The next day there was an inspection of our rooms – the white glove along the tops of doors and under beds type of inspection. We passed.

The second lesson came from a certain Corporal Kelly, our drill corporal. This individual was the quintessential drill NCO (Non-Commissioned Officer) who, although outranked by all of us, nevertheless was held in great respect, even awe. His conduct on the parade ground would have done credit to Buckingham Palace yet his unenviable task was to have us, “a shambles” of former university students, learn the art of marching and drilling to a level which would not bring disgrace upon the RAF. Amazingly he succeeded! His voice booming across the parade ground could strike fear into anyone not conforming. He was bound to call each of us “Sir” but he had a way of pronouncing the word which gave it a different meaning to the normal understanding. I recall the day when I was the practice parade commander. Whilst standing at attention in front of the whole course and holding my sword to the vertical, my memory failed me. “Sorry, Corporal Kelly – I have forgotten the word of command”. “Did you ever know? – SUUUR!” Oh, the ignominy!

Back Row Plt.Off. S. Mc. Tavlor. A.PIt.Off. W. S. Ashpole, Plt.Off. N. J. Gill, Plt.Off. A. C. Baker, Plt.Off. D. W. M. Jones, Plt.Off. N. J. Harvey. Plt.Off. J. M. McCracken, Plt.Off. T. N. Laing, A Plt.Off. P. A. Edney.

2nd Row Plt.Off. E. H. N. Turner, A.PIt.Off. B. C. Spikins, Plt.Off. V. Faulkner, Plt.Off. T. H. Stonor, A.PIt.Off. D. Holme, Plt.Off. P. J. Creigh, A.PIt.Off. A. Briggs, Plt.Off. K. P. Clarke, Plt.Off. E. D. Stein, A.PIt.Off. M. E. J. Archard.

Front Row A.PIt.Off. A. J. Davies. Plt.Off. R. k. Lewis, Flt.Lt. A. k. Amos, Flt.Lt. C. J. Barrey, d.f.c., a.f.c., d.f.m., Wg.Cdr. J. F. Manning, A.F.C., Gp.Cpt A. R. D. MacDonell, D.F.C., Sqn.Ldr. B. D. Davies, A.F.C., Flt.Lt. A. S. Tallet. Plt.Off. T. Maddern, A.PIt.Off. J. D. Aberdein, A.PIt.Off.. R. T. V. Kyrke.

We not only survived our basic training but we graduated. After all the cross country running, I had achieved the pinnacle of my physical fitness which was never emulated in all my succeeding years! Our next posting was RAF Ternhill in Shropshire for 110 hours in the Provost T1, then the RAF’s basic trainer. Here we were re-skilled in the arts of aircraft handling, navigation, night flying, aerobatics, formation, instrument flying, etc. in an aircraft somewhat more powerful than the Chipmunk of our university days. The course was divided into sections and at the end of each our progress was assessed. Anyone not making the grade was put on review and given an hour or two of extra flying to step up or fail the course! It was that simple! We also attended classes on leadership and officer qualities. As we neared the end of the 110 hours a few of us were bussed to an RAF medical establishment to be carefully measured. Some were tall men. I was not tall but I was long from head to butt! The reason for the visit was to ensure that we would fit into the Vampire T11. Too tall and the cockpit canopy would not close without hitting the top of the occupant’s bone dome and forcing the pilot to lower his head. Too long in the legs and the kneecaps would be removed during ejection. I was judged to be within limits for the Vampire but there were a couple who had to be trained to fly the Meteor, a twin-engined jet aircraft with more space for the pilots.

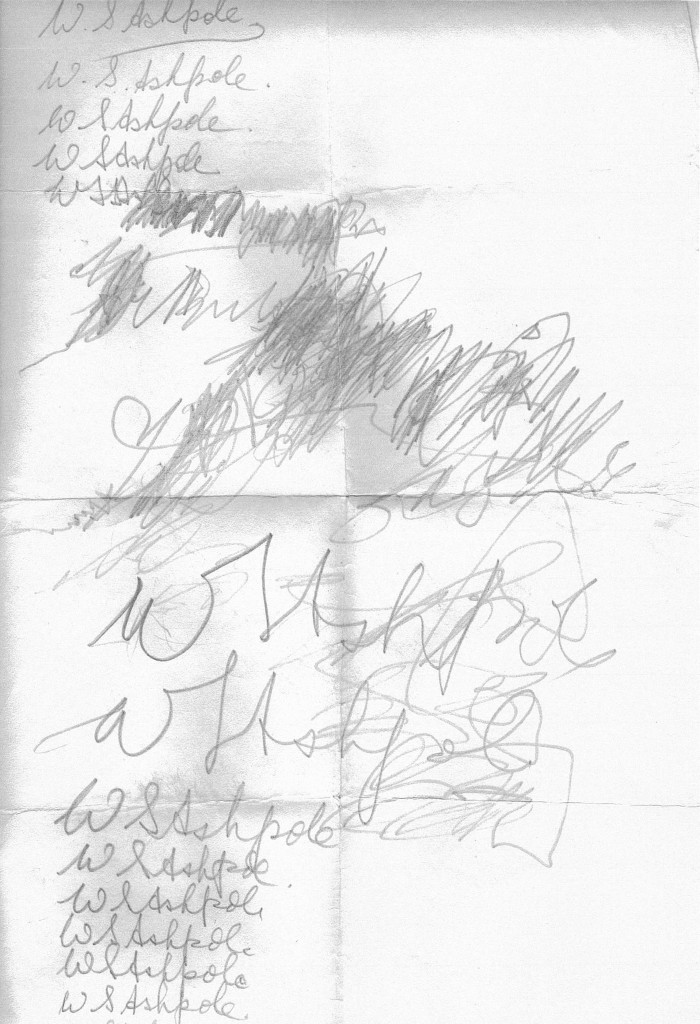

Demonstration of Anoxia

As an aside, one day we were all taken to an RAF medical establishment to experience the effects of anoxia (deprivation of oxygen). In groups of around 8, we were seated in a metal cabin and told to don oxygen masks. It was then explained that the air in the cabin would be evacuated and each of us would be given a simple task. Mine was to write my signature on a sheet of paper starting from the top and continue repeating writing down the page. The air was evacuated and then the oxygen supply to our masks was switched off. A few minutes later it was switched on again. The result of this exercise was absolutely stupefying and a copy of my efforts is shown below. The amazing thing is that one has absolutely no recollection of losing consciousness or an awareness that one has just recovered from the unconscious state. It explains a number of tragic aviation incidents including the loss of a whole airliner full of passengers over Greece and an executive jet which flew across North America until it crashed. The crews and passengers would have had no knowledge of what was happening, the onset of anoxia being so insidious.

Having survived basic flying training at Ternhill, we were posted to RAF Oakington near Cambridge for advanced flying training.

The original version of the Vampire flew at the end of the Second World War. The T11 was a development of that original single-pilot Vampire but with two seats, side-by-side, one for the student pilot and one for the instructor.

One gained access to the cockpit by climbing a ladder. I recall peering down into the small dark hole in which I would spend 110 hours. I had serious doubts as to how I could possibly fit into such a confined space. Then the truth dawned that not only I, but also my instructor, would have to fit into this hole. One squeezed down between the dashboard, throttle and ejection seat. It was very snug with everything to hand. It became very apparent why we had had the visit to the medical establishment to have our bodies carefully measured.

One of the first impressions with the Vampire was how quiet it was. Instead of a large radial petrol engine and a propeller a few feet in front of one’s nose, there was a quiet whine to the rear of the aircraft reminiscent of a vacuum cleaner. Climbing away from the ground reminded me of becoming airborne in a glider.

The Vampire had a couple of vices. The first was that its engine was very slow to accelerate from low speed. This was due to the fact that it had a large and thus heavy centrifugal compressor at the front of its Goblin engine, an engine which was not far removed from the one Sir Frank Whittle, the inventor of the jet engine, had built prior to WWII. On most aircraft, during the approach to landing, one would normally have the engine throttled back. Should one find oneself undershooting the threshold of the runway it would become necessary to open the throttle to arrest the descent. Opening the throttle too rapidly on a Vampire with the engine at a low rpm would produce a loud protesting rumble from behind the pilot’s seat and a possibility that the engine could stall resulting in a total loss of power and the inevitable crash. The trick was to lower plenty of flap on the final approach to create more drag thus necessitating higher engine rpm to maintain speed. This took the engine out of the stall region and into one where a more rapid acceleration was possible.

The other vice was spinning. Although the Vampire had twin tail fins, the total aerodynamic vertical fin area was still rather small. Good rudder force is essential to stop an aircraft spinning. Vampires had been known to enter spins and despite the valiant efforts of the pilots had continued spinning into the ground. One normally commenced a spin exercise between 20,000 and 30,000 feet. If recovery from the spin had not been achieved by 10,000 feet then ejection was mandatory. Soon after we arrived at Oakington an aircraft crashed following a spin. Tragically, the pilots perished. All spinning was stopped. A few weeks later all pilots assembled in the officer’s mess for a briefing on spinning. The message was that the Central Flying School, where instructors are trained, had solved the spinning “bogey”. Instruction was then received on the “foolproof” method of recovery from a spin. Spinning recommenced. Within a month, one of our course members, Vic Faulkner, flying dual, entered a spin and although using the new foolproof technique, he and his instructor were unable to stop the rotation. They ejected safely. Vic landed in a field and a passing motorist stopped to pick him up. As they drove away the driver turned to his son in the back and said “you always wanted to see a man come down by parachute-say thank you to the man”!

Escape and Evasion

We were all subjected to an experience whilst at Oakington that was something else – an Escape and Evasion exercise. We were given a one-piece fatigues type uniform and were taken in lorries to somewhere, I know not where, but possibly Lincolnshire. Divided into teams of three, we were given a compass, a map and a torch per team and everyone received a survival pack of food items. By food I mean a bar of chocolate, an Oxo, a few biscuits, and so on. and a bottle of water. Doug Aberdein was one of my three and, if memory serves me right, Brendan Spikins was the other.

Now it would seem reasonable in such circumstances for each member of the team to have one of the three navigational tools. And so it was in our group. But soon after dusk on the first night we ran into the enemy, soldiers, or rather the enemy ambushed us! We scattered in the dark. Now a compass is a very useful item of kit but not in pitch black with no torch or map. A map is a vital item for navigation but useless without a torch. A torch is really useful but of little use without a map and compass. And so the three of us blundered on our separate ways in the hope that we were heading in the right direction. As daylight broke we met up again and even joined another team. Travelling by day was not a good idea as we could be seen more readily by the enemy. We found a barn full of hay bales and decided to rest. Now hay bales are very inviting so we bedded down. Sleeping was a challenge compounded by the fact that the hay was damp. Our clothes became damp and that, added to the cold, left us very uncomfortable indeed! It gave us a very healthy respect for those downed aircrews in active service.

When one is cold it is surprising how hunger takes hold. It was not long before the entire contents of the survival pack had been consumed. Eating a raw Oxo is an experience! Even though the whole of our exercise took place in two days, our very limited deprivation from food and warmth began to cause loss of energy and a lowering of enthusiasm.

We arrived at the rendezvous and a dead rabbit was tossed at our team. For Brendan Spikins and me this meal was as useful as a rubber screwdriver. Fortunately, Doug Aberdeen had a degree in agriculture and had worked on a farm. He deftly skinned the animal and cooked it, after a fashion, on an open fire. That rabbit was one of the most memorable meals I have ever eaten-it was delicious! I learnt, by our brief exposure, to have the greatest respect for anyone who had survived in a life threatening environment for any period of time without the comforts we usually take for granted.

AWARD OF THE RAF WINGS BREVET

PASSING OUT PARADE – FRIDAY, 10 MARCH 1961

NO 5 FLYING TRAINING SCHOOL – ROYAL AIR FORCE OAKINGTON

We completed the wings course at RAF Oakington with 110 hours on the Vampire T11 in March 1961. This was a very proud moment for all of us on the course. We felt, with some justification, that we had achieved something very worthwhile and extremely demanding.

Some weeks prior to the end of the course we were invited to fill in a form stating our preference for the type of aircraft that we wished to fly. I put helicopters as my first choice. As I recall it was because helicopters were not aerobatic (then) but, of greater importance, offered the best potential for “freedom” in flying compared with the very controlled regimes of the other types. The two most likely roles were either Search & Rescue and support of the Army in the field. The “freedom” I mentioned is very apparent. In S&R, the pilot takes off and he alone has total responsibility, with his crew of a navigator and winch-men, to find the survivor, plan the rescue and then effect the saving of life. Supporting the Army is likewise a case of taking off to meet up with the Army unit then carrying out whatever task is required. In neither role can the pilot call upon help from say, air traffic control or other agencies. Other members of the course were posted to fighters, maritime and light bombers. Four were posted to the V-Force, an assignment which involved sitting in dispersal for hours on end, very little flying, and limited actual handling of the flying controls on one’s first tour. Worse, if so called upon, to take off within the 4 minutes warning time with the intention of wiping out millions of Russians in the sure knowledge that the country and loved ones back home would no longer exist!

Where have all the young men gone? Wings course reunion at the RAF Club in London 40 years after graduation at Oakington. Left to Right: Back row: Rod Adam-Smith; Bill Ashpole; Stew Taylor; Jack Davies; Alan Baker; Norman Gill. Middle Row: Doug Aberdein; Brendan Spikins; Tom Stonor. Front Row: Tony Davies; Dick Kyrke; Vic Faulkner. Sadly, editing this in 2020, I have to report that a number of my former colleagues have “got airborne” for the last time

In April I reported to RAF South Cerney for the helicopter conversion course on the Bristol Sycamore.

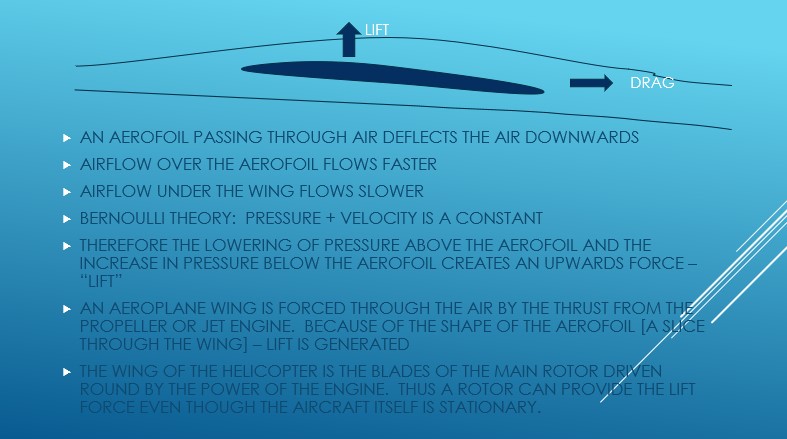

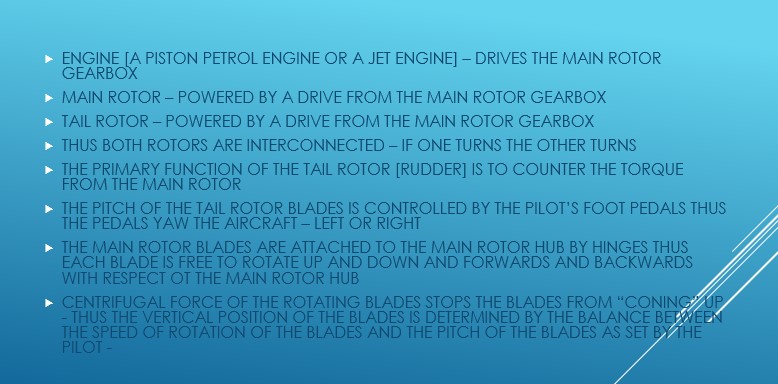

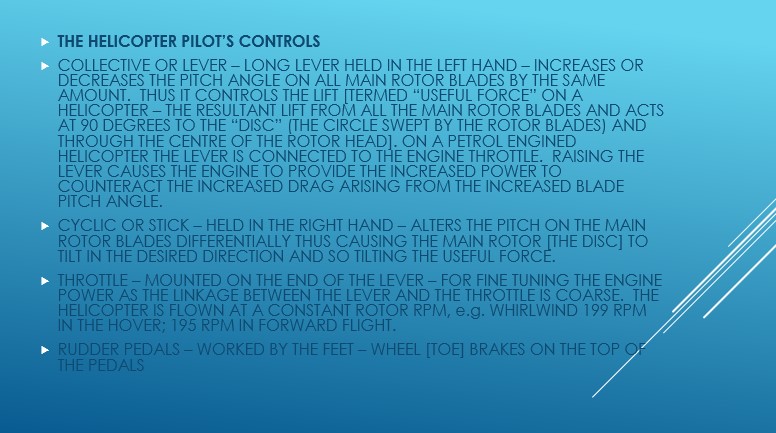

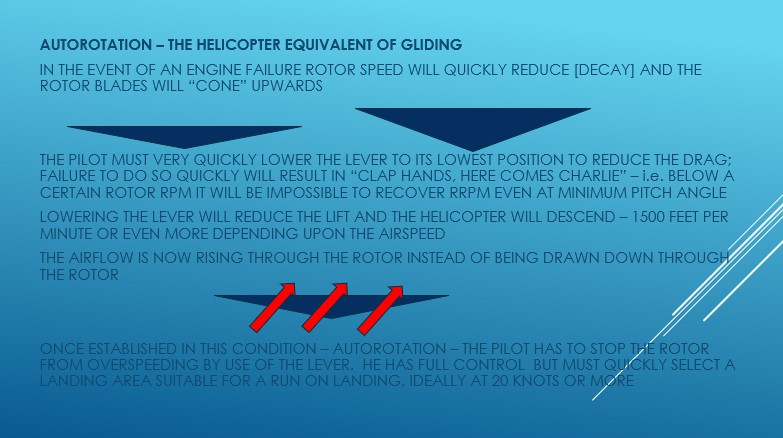

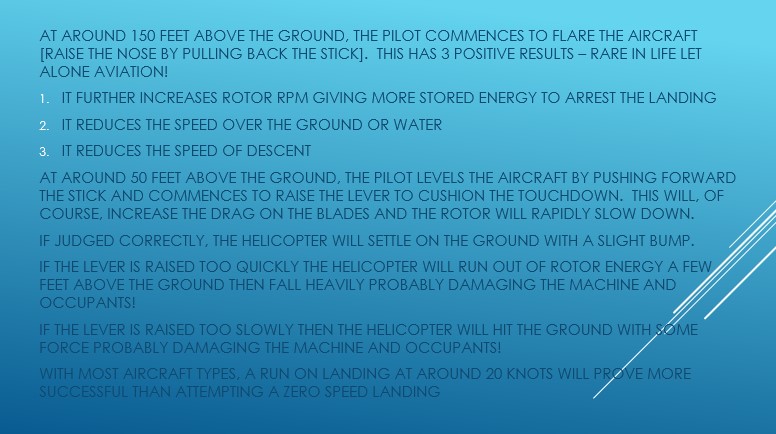

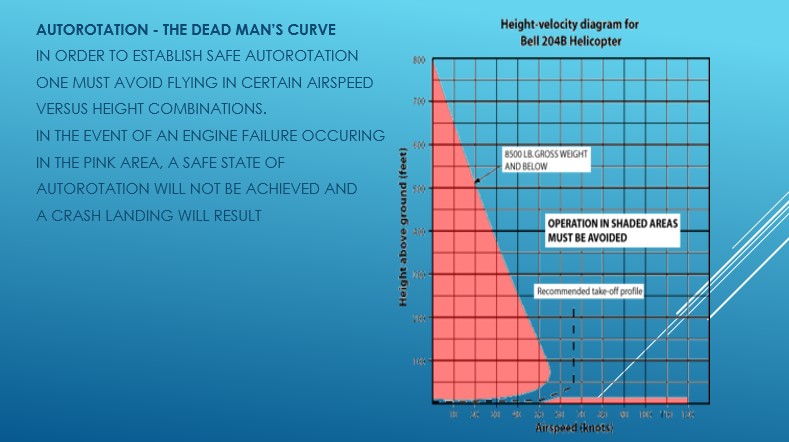

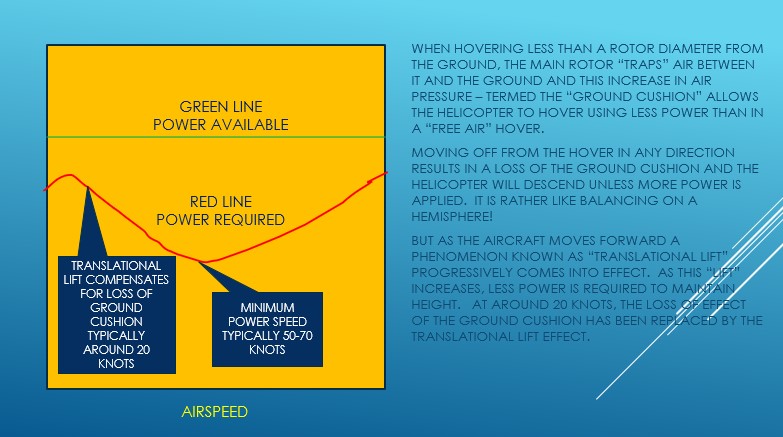

Now handling a helicopter is very different from handling an aeroplane. There is the familiar STICK and RUDDER PEDALS but instead of the simple THROTTLE of the aeroplane to adjust power, there is a long LEVER with a twist-grip THROTTLE at the end of said lever, both of which must be moved in a coordinated manner to alter the lift. This was the case on the early helicopters, such as the Sycamore and other helicopters of its era, powered by piston engines (petrol). Later, when gas turbine powered helicopters were developed, rotor speeds were governed by a simple computerised system. By simple, I mean they were relatively sophisticated for the day but very simple compared with even a laptop of today. A helicopter is flown at a constant rotor speed (RPM), possibly with small exceptions to increase range in the cruise. Unlike an aeroplane, a helicopter is both statically and dynamically unstable so it cannot be trimmed in flight to be flown hands-off the controls. EVEN IN STRAIGHT AND LEVEL FLIGHT, THE PILOT MUST CONTINUALLY ADJUST THE STICK AND RUDDERS AND, UNLESS THE ROTOR SPEED IS COMPUTER CONTROLLED, THE LEVER/THROTTLE COMBINATION MIGHT ALSO NEED ATTENTION. Below is a simple explanation.

There are other aspects of flying a helicopter which are different to aeroplanes so to assist readers who are not familiar with the type, I include the following diagrams and text to provide some explanation.

The lever on a Sycamore is positioned between the seats of the pupil and instructor and the throttle is set at right angles to the lever so that it can be shared by both pilots. This photo was taken at the Boscombe Down Air Museum.

The Sycamore, a 5 seat aircraft, was a far from ideal machine on which to learn the mysterious art of piloting a helicopter. Compared with the Hiller 360, as used by the Army at Middle Wallop for their basic helicopter training, the Sycamore was a very complex machine.

It had been designed as a communications aircraft and in order to make it fly level, the main rotor shaft was offset longitudinally and laterally. On take-off the pilot had to hold the stick an imaginary four divisions rearward and one division to the right and then centralise as the wheels left the ground. These imaginary four and one divisions had to be modified for wind and sloping ground.

The Sycamore was very prone to ground resonance, the condition on take-off or landing when half the weight is on the rotor and half on the wheels. Any slight mishandling at this point could induce ground resonance, a condition leading to a rapid build-up of vibration in the helicopter which, if left unchecked could develop to the “natural frequency”* of the machine and would result in its destruction. (*remember the Tacoma bridge in the USA which self-destructed when subjected to wind of a certain speed and direction).

Another vice of this machine was the centre of gravity compensator. This consisted of a liquid-filled tank at the front and another at the rear of the helicopter with an electric pump with which the pilot could transfer the fluid to alter the centre of gravity of the machine. Failure to be fastidious in take-off or landing checks could result in the aircraft being totally beyond its trim limit with disastrous results.

The Sycamore had wooden blades and large changes of ambient temperature could twist the blades requiring them to be re-tracked (a process requiring an engineer to make adjustments to the main rotor such that the rotor tips are made to pass through the same point in space).

In spite of all these pitfalls, it was said by those who truly mastered the beast that this was a pilot’s aircraft. I was not one of those! In fact, during my training, and immediately following a gross mishandling incident requiring him to grab the controls, my instructor, Roy Garwood, said “Bill, are you sure you want to be a helicopter pilot? Would you not prefer fighters?”

My final handling check was conducted by Squadron Leader (Bushy) Clarke – a helicopter pilot of formidable reputation and quite a character with a huge Battle of Britain moustache. My final flight at South Cerney was on 21 June 1961 at which point the now “Flying Officer” Ashpole was considered by the RAF fit to be let loose on a squadron, in my case no. 225 Squadron based at RAF Odiham in Hampshire.

However, before that posting I had another event of even greater importance – my marriage – to my fiancée, Margaret. I borrowed the ceremonial swords from the RAF for my best man, Doug Aberdein, and myself for a wedding in uniform; the wedding was also attended by Brendan Spikins, another great friend and colleague. A tribute to Margaret appears in the next section.

![vamp[1]](http://www.ashpole.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/vamp1.jpg)

Hi,

I found your site quite by accident after typing in Dad’s name (Brendon Spikins). Sadly Dad passed away in November 2004. I read with interest and I wondered if perhaps you had any other memories of Bren you might be able to share? I know so little of his life before I was born…..

Best wishes,

Jeremy Spikins

This post was replied to privately due to the confidential nature of the comment

Have read your artical regarding 225 Squadron. Really enjoyable. You mention my brother John Brundle briefley. He and Croocker were killed 30th July 62 in Germany. I know all about the crash etc but wondered if you could fill in any gaps regarding him and his fellow pilots in earl 62 at Odiham. Do you know what happened to Ed Forsyth by any chance? Kind regards Mike

Replied to privately due to the nature of the enquiry

Replied to privately due nature of request

Hello William,

Thank you for turning in today . The website is great even if I have as yet to read all !! Makes my 200+ hours look silly but I guess if you have flown anything as pilot in

command it still apply.

Speak soon.

Pat

Hello Mike,

I stumbled across Bill Ashpole’s website and saw this “Do you know what happened to Ed Forsyth by any chance? Kind regards Mike”

I was probably best friends with John and yet I didn’t know he had a brother – or my memory has failed me.

I left the RAF after 8 years and joined Qantas Airways. I moved to Sydney and flew with Qantas for 29 years. I still live in Sydney and have been retired for 19 years.

I was christened Adam but my folk called me Eddie! I took the opportunity to change back to my proper name when I moved to Australia so everyone oput here knows me as Adam.

Would love to hear from you.

Cheers,

Adam Forsythe.

Does anyone remember a South African name Ivan Spring who was stationed at Oakington late 50’s – early 60’s? He was then posted to Marham on Valiants. I lived in Cambridge and met him there. I would be grateful for any information.

Dear Sue – I regret to say that I do not remember Ivan Spring but let us hope that someone visiting the blog may respond. Good luck Bill Ashpole

Can this please be forwarded to Sue Bennett?

I worked with Ivan in Johannesburg in the 1980’s and we became friends.

Please pass on my e-mail address.

Bill,

Stumbled across your blog by accident.

1. I see you have left me as N J Grill in the Ternhill Photo – same as the original.

2. The ? missing name at the reunion is Alan France who never graduated due to an ejection injury. I visited him in Washington state three years ago. He was not in great health and died the following year.

Cheers

Dear Norman – What a pleasure to hear from you after all these years and to learn that you are still with us. Sadly, so many are not! Of the many memories of you I recall your musical expertise – the ability to pick up anything – even a piece of tubing and play a tune! You were, and presumably still are, a gifted musician.

I will add a note to the photo to correct the mistake in your name and also add Alan to the reunion photo. Doug Aberdein also told me of the ? I am in touch with him again after the intervening years. It is so sad to hear of the departure of Alan, another former colleague. There may not be many of us left! Best wishes to you and yours. Bill Ashpole

Hello Mr. Ashpole. I am Bren Spikins sister. Still close to his wife and family.I miss him greatly and on looking up info on his career and happy times in the RAF i have been dismayed to read huge inaccuracies which I feel must be what I believe are called Scams. There is something which comes up under lar Brendon Spikins which shows a picture of Bren but a totally inaccurate report on him. I just wondered whether you might know what one can do about these things. It seems so disrespectful of someone. I am glad to read of your friendship with him and would so appreciate any help you might be able togive me………….thank you Hazel.

Hi. Only just come across yor info. Great to hear your alive and kicking. I remember you well. You were a great comfort after John was killed. You even took me out in johns Morgan car on the eve of the funeral in Germany 1962. We visited 225s hanger on the other side of the airfield. I ended up as a flt Sgt. Supplier and completed 27 yrs. service.

I attended the unvailing of the helicopter memorial at Odiham in 2005 29th July. With my wife and father. My wife died of the big C in 2008 followed by dad the following year aged 89

Dear Mike – I am very pleased to hear from you but sad about your double loss. Those must have been very testing months. I note that you not only joined the service but spent a sizable part of your working life in the RAF. The influence of your father and his love of the RAF found its target. I have never been back to Odiham post my 5 years RAF service in 1964. I do belong to “The Old Rotors” – a group of helicopter pilots most, of not all, who served in the Borneo campaign but after my time there. Best wishes Bill Ashpole

Does anyone have any memories of Don Brims, as his second wife i know very

little of his time in the RAF

I would love someone to share their thoughts of Don, with me and our two

daughters.

Thank you.

Sue Brims

Hi, I was wondering if Doug Aberdien (above) was based at RAF Khormaksar in 1961 on SAR with Bristol Sycamore helicopters.

My name is Brian (Smudger) Smith and I used to wake a Doug Aberdien up in the officers mess at 0400hrs for his 0430hrs patrol. Please let me know if this is you, because it would be good to have a catch-up.

Hi Brian

After the helicopter conversion at South Cerney and my marriage, at which Doug was best man, I lost contact for some years. He did go onto S&R but I thought that was at Chivenor. He may well have gone to Aden. I doubt whether there are two Doug Aberdein’s. He was one of a kind!! I think you can be sure he was the guy you used to wake.

I regret to say that Doug did not answer the email I sent him which contained your comment on my website. I have tried phoning him but the number is now defunct. If he should answer the email, I will let you know.

Best regards

Bill Ashpole

Hi Bill, Many thanks for trying to contact Doug, I could tell you quite a few stories about our time at RAF Khormaksar, but they are not for the public domain. please give him my e-mail address if and when you can. One of the Sycamores the he used to fly is an exhibit at Weston-Super- Mare helicopter museum although it is in a different roll. I look forward to checking my e-mails.

Kind regards,

Brian (Smudger)Smith.

Hello again, Bill.

I found this site again when referred to it by a friend looking for someone else.

You will be sorry to hear the Brendon, Doug and Stew Taylor are now all deceased.

Hope you are OK though.

Regards

Norman Grill

Hiya just thought You might like to know a bit about CJ Barrey RAF, who I am guessing was at 1 ITS as an instructor (?).

I am related to him and would be happy to share more if your intrested, but briefly –

He was Nicknamed ‘Bush’ Barrey and like Mick Martin and many many others was an Australian serving in the RAF. He was born in a Suburb of Adelaide South Australia and His Brother Ray joined the RAAF in 1940 and was Killed in November 1941 on board HMAS Sydney as the Seaplane Pilot (Another Family member was on board at that time who was Regular Navy and was also killed, in point of fact 7 members of the Family served in that war, of which 6 were killed, 4 RAN and 2 RAAF – John was the sole survivor).

He enlisted with the RAF in 1938, after working his Passage to England from Australia and trained as an Observer. After Completing His training he was Promoted to Sgt and posted to 113 RAF Squadron in the middle east. He was awarded the DFM and served with the Squadron flying Blenheim Mk I and later Mk IV Aircraft until he was sent on a rest Posting as an Instructor. He then earned the AFC and was Recommended for Pilots Training, after Completion of which He was Commsioned and Posted to 450 RAAF Squadron flying Kittyhawk Fighter Bomber Operations in Italy, and later being Posted again to 250 RAF Squadron flying Mustang Fighters.

By wars end he had Completed 175 Operations and been awarded the DFM, AFC and DFC.

He Remained with the RAF until 1974, his last posting helping to train Saudi AF pilots how to fly the Lightning Fighter Jet. After leaving the RAF he returned to Australia and is now Deceased.

Stephen.

NSW Australia.

Hi Stephen – thanks for your comments – what an interesting history -sad about the fatalities. Bush certainly spent a long time in the Service and did well to convert from very slow to such high speed aircraft. My website/blog receives many visitors so, unless you advise otherwise, I will leave your contribution on the site in case someone remembers Bush. My blog has a predominantly helicopter theme. You might find another website with more general RAF/aeroplane musings which could benefit from having your notes.

Best wishes

Bill Ashpole

…. Sqd Ldr CJ ( Bush ) Barrey DFC AFC DFM is my father .. 13/12/1919- 28/5/2006 Adelaide South Australia – Lest We Forget.

Dear Barbara

I really appreciate you taking the trouble to comment on the website. As I said in the text, everyone thought your father a real character and one who had made a very significant contribution to the world of helicopters in the Royal Air Force. I only met him on this one occasion but I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say he became a bit of a legend! My very best wishes to you and your family.

Bill Ashpole

Hi Bill,

Like many others I stumbled upon your site after googling Vampires RAF Oakington. I very much enjoyed reading it. It brought back a lot of happy memories. After our reunion at the RAF Club, at which time I was still flying with DAN AIR I think, they went bust. I was 57 by then and flying jobs were thin on the ground at that time and I was afraid my flying days were over. However a few days before the airline finally folded, I had popped down to the Dan Air HQ in Horley to say farewell to a few friends, and was speaking to someone there in the general office, when the office manager Nobby Clarke who was on the phone said loudly-“I’ve got just the person for you”. Then he called to me “Vic. Someone here is looking for a 748 captain”! Thus I had a 2 minute interview and got the job. And thus I joined Euroair flying mail mainly from Stanstead to Aldergrove several nights a week.

A year later I moved to Liverpool flying newspapers to Aldergrove an finally ended up with Gill Air in Newcastle flying the Shorts 360 where I stayed happily until retiring 3 months before the millenium.

Since then I have been a gentleman of leisure. If I had known I was going to last so much longer I would have looked for further employment!

The only other person that I have any knowledge of is Jack Davies who unfortunately died 3 or 4 years ago.

Thank you for your enjoyable website Bill

Vic

Replied to privately to Vic Faulkener’s personal email address

Hi Bill,

Just for your info in the photo taken of the course reunion at the RAF club, the fourth person in the back row is not Alan Franc but Jack Davies. Not originally on our course but joined us on Vampires.

Best wishes,

Vic Faulkner

I have this on my wall… https://twitter.com/1sostatic/status/1185902713848107008/photo/1

Hi Al

Lovely to hear from you after all these (58) years and hope you are enjoying the best of health. Do you have a copy of the complete cartoon? If so, if you wish, I will include it on my website. I note that it says Syerston/Oakington. I am wracking my memory as to why Syerston is mentioned. Did the course split to Ternhill and Syerston after South Cerney to be reunited for advanced flying training at Oakington?

Best wishes

Bill Ashpole

Dear Bill

Not sure on split, I’m the son of the now late K.P. Clarke (Ken…aka Nobby)

I saw this and thought I should post something in his memory.

I have a lot from his Vulcan Bomber days but very little from UAS other than that one cartoon. I believe that cartoonist did him again at the “Royal McKenna dinner” at ETPS Boscombe Down… he was Chief Ground Instructor; a title that made me chuckle, as you guys are supposed to be up in the air, hurling hardware around the sky.

Dear Al

My apologies for not realising you were the son and not the father. Us old guys can get easily confused. Nevertheless, delighted to have you comment on the website. I find it particularly moving when children, or even grandchildren, of my former colleagues, make contact. If you have the cartoon, please scan it and email it to me. I would be pleased to include it as it honours the memory of your father.

Best wishes to you.

Bill Ashpole

Just found your site, You may remember me from BCAL Days when I was Manager Flight Dispatch and later when I worked for IATA in the AS/PAC Regional Technical Office. Grateful if you could contact me by email. To exchange info. I joined the RAF on a Direct Entry Commission and was on 132 Course at South Cerney and then went to Ternhill and then Oakington, Unfortunately I got trapped by the visiting CFS team and became a navigator.

Replied to privately.

Hello Bill,

Nice to see how you’ve fared since leaving school. I see you’ve included a photo that I took of Chris Hogg, Ray (Tubby) Achurch, Harry Carter, youself and Roy Woolley. I’d be interested to see if this gets through to you, so please let me know.

Best regards,

Barry Kraushaar – Former Cadet Sergeant, Royal Liberty School 1949/56

Replied to privately

Bill,

Glad to see you still have a copy of the ‘photo I took when we did some Anson flying during our RLS Cadet days. Hope you are well and would be pleased to hear from you.

Barry Kraushaar – Ex Cadet Sergeant!

Replied to privately

Hi Bill,

Like a number of others above, I came across your site entirely by accident, and almost fell off my chair when I saw the photo of ourselves as ULAS members, during those halcyon days of our youth, with me on your right, and Mike Gibson on your left. I learned from Mike Harding, with whom I Facetimed yesterday that sadly Mike Gibson passed away last May, 2020, after a great career in the RAF, rising to AVM. He was also an accomplished musician, an arena he pursued after retiring from the RAF.

I am long retired from McDonnell Douglas, now part of Boeing, after an enjoyable career on the Commercial side of the company.