Caution on copyright should you wish to use photographs and diagrams from my website. I have included attribution wherever known and attempted to seek permissions from authors/owners of copyright who could be still found. This was not possible in all cases as the source of the photo was unknown or no longer in existence.

Following completion of the helicopter conversion course, one of life’s really major event took place – my marriage to Margaret – a marriage which lasted 53 years until she departed in 2014 following three years of an awful lung condition, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) – of unknown cause and no known cure. She bore our first daughter, who died after an hour in the Louise Margaret Military hospital in Aldershot, another daughter and two sons. She was loved and admired by all who knew her – the best wife, mother, grandmother and great-grandmother. Incredibly brave, faced numerous medical challenges and extremely tolerant of my failings.

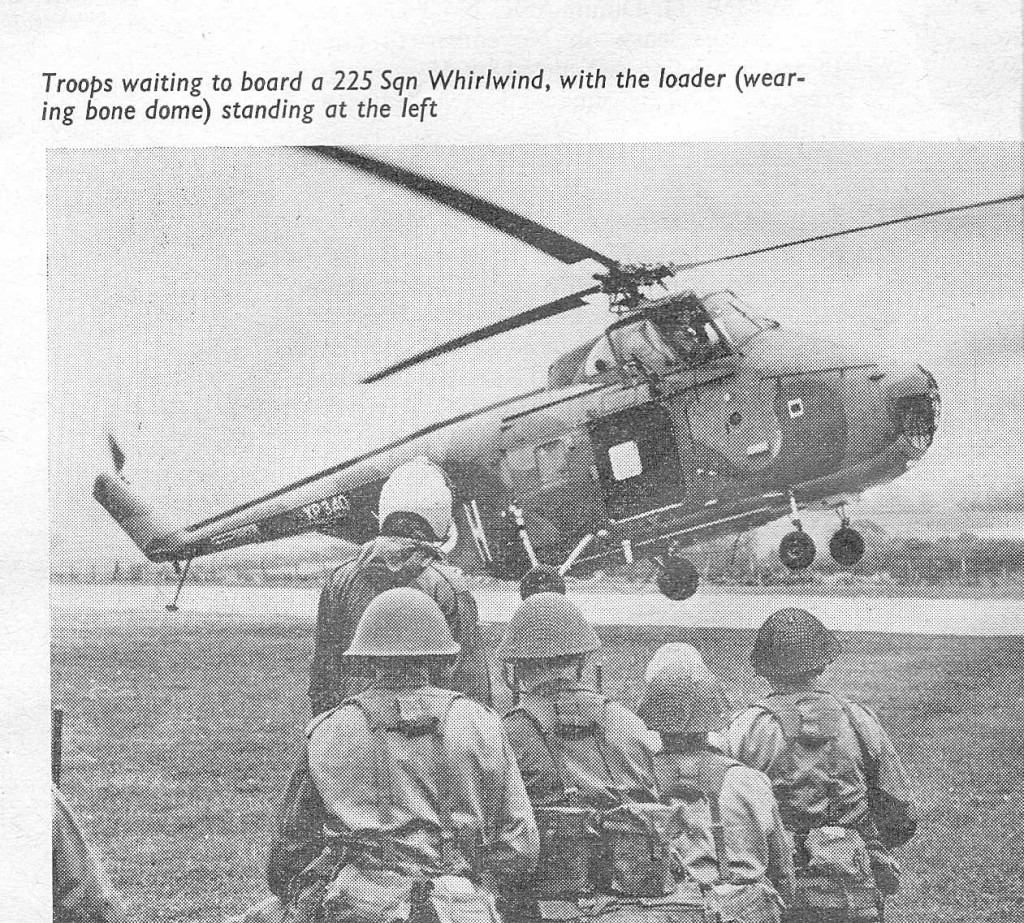

Three of us graduating from the helicopter course at South Cerney were posted to 225 Squadron at Odiham in Hampshire. We each had a little over 32 hours of helicopter time. RAF Odiham was, and still is (2019) the headquarters of 38 Group whose role is to support the Army in the field. The average age of the pilots on the Squadron at that time seemed to be 65! There had been a sudden switch of RAF policy from having only over 35-year-olds flying helicopters to only under 35-year-olds. Someone, in the higher echelons of power had probably sensed that helicopters would become more and more important in the defence of the Realm. Squadron Leader Alan Twigg was the Squadron commander – a highly respected figure. It was an interesting baptism into squadron life to have such experienced helicopter pilots, some of whom had served in the Malayan campaign, as one’s colleagues and they were very generous to us young sprogs. Our role in 38 Group meant wearing “Boots – shocking heavy!”, gaiters, and camping out on various exercises – a Boy Scout’s rather than a gentleman’s life! I recall one exercise during a freezing winter waking up in my Igloo tent on the airfield at RAF Waterbeach. There was ice on the inside wall of my tent and empty rooms in the officer’s mess!

Squadron life

At first our hangar was in the main conurbation of hangars at Odiham but then we were banished to one on the far side of the airfield. The biggest frustration for a young pilot was the lack of flying hours available, typically under 10 per month unless there was an exercise.

Westland Whirlwind S55 – piston engine – typical of one of those flown by 225 squadron with a winch, also a hook for carrying underslung loads

A Mk 10 Whirlwind – Gnome engine – as equipped to 225 squadron replacing the piston-engined Whirlwinds

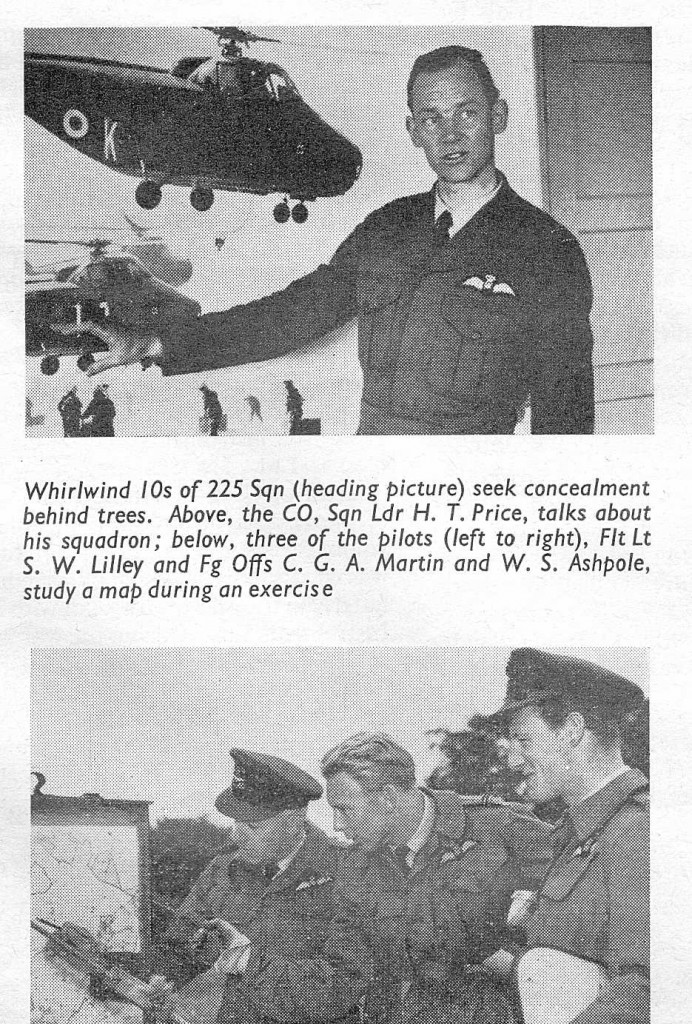

My initial flights were on the Sycamore but a conversion to the Mk 2 and Mk 4 Whirlwind quickly followed. My logbook over the next three and a half years shows a list of squadron pilots such as Don Brims, Bill Burke, Master Nav Griffiths, Stan Lilley, Alan Brew (who was on the course with me at South Cerney and years later in British Airways Helicopters), Barney Swinton-Bland, Lofty Marshall, Pete Pekowski, Bill McEachern, Tim Carbis, Phil Cooke, Master Nav Mitchell, the Squadron navigator Jim Sinclair, John Barlow, Alistair Martin, Brian Danger, John Bleaden, Mike Ginn, Eddie Forsythe, Terry Laing, John Wallace, Chris Paish, George Warren, and flying officers Brundle, Crocker, Lloyd and Flight Lieutenant Harvey. A few months after I joined 225, Alan Twigg received a new posting and the new squadron commander arrived – Henry Trevor Price – not to be confused with “Bathroom-scales” Price and other squadron leaders with the same surname! Looking back on my days in No 225 I have a feeling of great privilege to have known such men. Most had their idiosyncrasies but it was a pleasure to be part of the camaraderie and professionalism.

After a couple of months on the squadron something wonderful happened. Hitherto I had flown helicopters as a man controlling a machine. But one day, whilst still flying the petrol-powered Whirlwind, I suddenly realised that I had become one with the beast! It is difficult to explain what I mean but I discovered that I was no longer moving the controls with my hands and feet – I was now an integral part of the process of flying through the air – the machine did what I willed it to do! It was a step-change in my piloting abilities.

Flying was generally very interesting and demanding. Working with various units of the Army, we transported troops in the cabin and had them exit by landing, low hovering, abseiling and parachuting. We flew military and civilian casevac flights into such hospitals as Stoke Mandeville. We flew all kinds of underslung loads ranging from rations to small field guns. On one occasion at Gillingham, I had a rubber inflatable boat as a slung load. The thing went berserk over 30 knots! We dropped dummy mines with large rubber skirts to slow their descent. As a twist on this we had a platform fastened to the side of the helicopter with a drop-down ramp. We had to fly slowly with the end of the ramp touching the ground as mines were fed from the cabin onto the platform to slide down the ramp onto the ground. Exercises took place in all the military areas on Salisbury Plain, Brecon, Somerset, etc. Some took place in Northern Ireland and even on the mainland of Europe. We also practiced winching survivors. Navigation was by eyeball and topographical map, quite difficult when the right hand cannot release the stick as, with full servo powered controls, it would just fall by gravity in whichever direction it was taken, with the main rotor and thus the helicopter following suit. It was possible to apply the friction lock to the lever, held in the left hand. This was sensible in the case of the Mark 10 with its computer-controlled rotor speed. In the case of the piston-engined aircraft one had to lock the throttle (at the end of the lever) as well but doing this had its disadvantages and even dangers. So essentially, the Whirlwind, like the Sycamore, was a handful with no free hand to hold a map and the necessity to “fly” the aircraft continually without let up, a helicopter, unlike an aeroplane being both dynamically and statically unstable. These military machines had no automatic stabilisation system. No Whirlwind, except perhaps those of Queens Flight, had any form of heating or cooling for the pilot or the passengers!

I am indebted to Tim Carbis, the son of the late Tim Carbis, one of the members of the Squadron, who drew my attention to the following two URL’s. The first is an account of a royal visit to Odiham and the second is an exercise, typical of our work:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0xuNZG7X5aE

https://youtu.be/o9M27PpSCAw?t=4

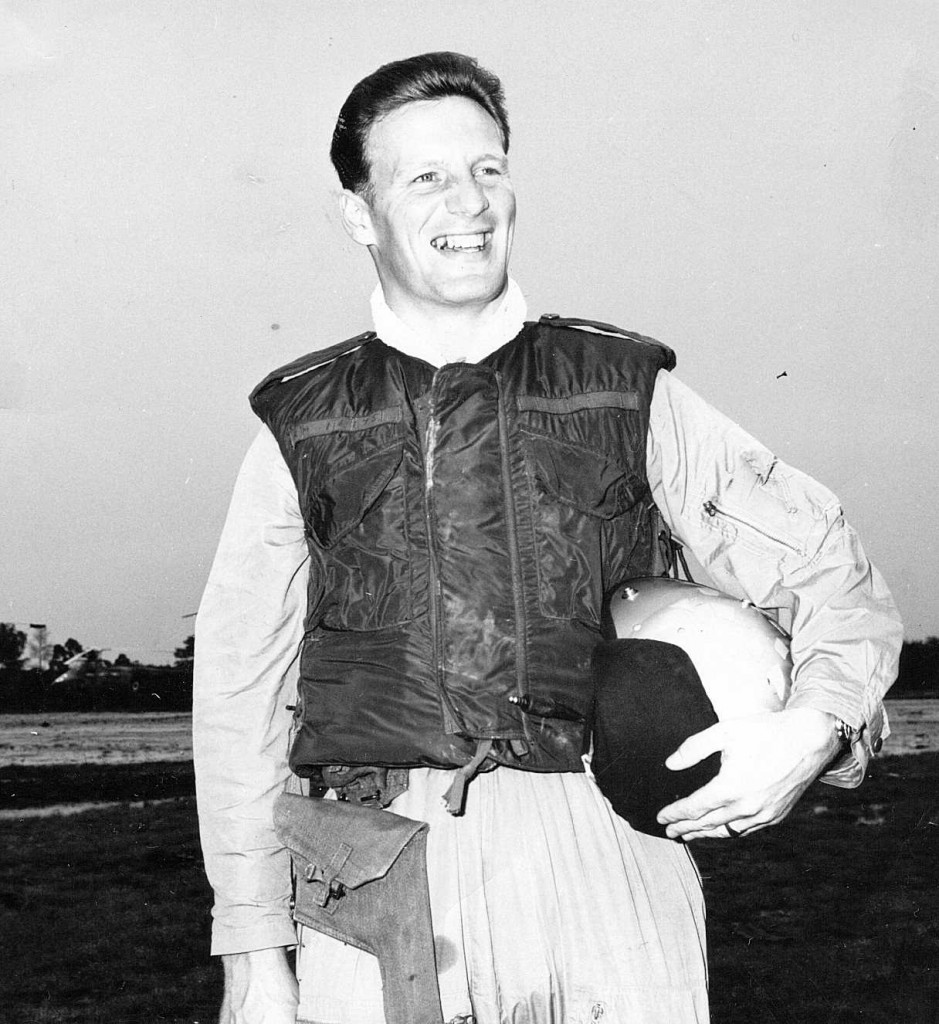

THE AUTHOR FLYING – LAYING MINES DOWN A CHUTE AT GILLINGHAM (PHOTO ON FRONT PAGE OF “THE SOLDIER” MAGAZINE)

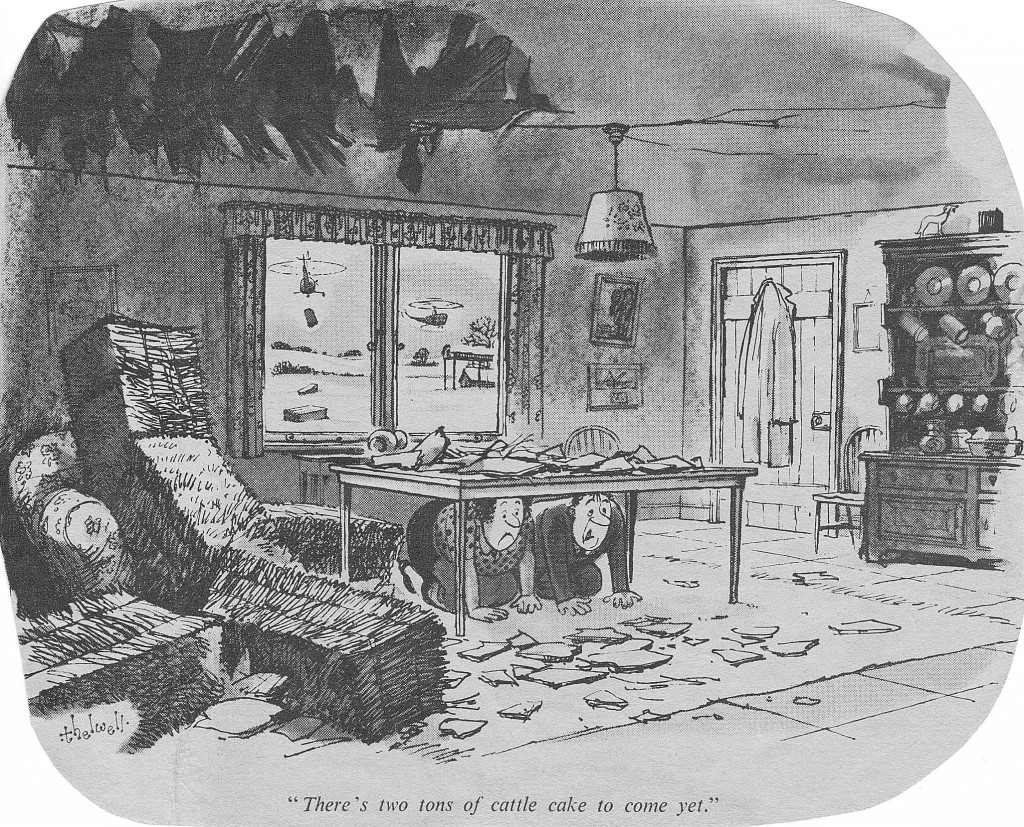

In January and February of 1963 the UK suffered some extremely cold weather with many areas cut off. No. 225 Squadron was called upon to assist and I flew to Exmoor, Dartmoor and to the Elan Valley in South Wales mainly to carry fodder to animals perishing in deep snow in the fields.

I had a trip to Fylingdales to carry a transmitter as an underslung load across their range whilst I was tracked, fortunately passively, on the early warning radar for calibration purposes. One year the Squadron took part in the Farnborough Air Display. A flotilla of Sycamores, Whirlwinds, Belvederes and STOL aircraft arrived to disgorge troops and equipment in front of the spectators. On one occasion, Squadron Leader John Dowding, commanding the Belvedere squadron flared* to a halt in front of the crowd. Unfortunately, his flare was a bit too gung-ho and the aircraft slid at an angle of 60 degrees backwards into the ground. The moment was captured by the Daily Mirror whose front page had a photograph of a mist of dust and mud with the ghostly outline of the plan view of a Belvedere shedding pieces of rotor blade! I believe the caption read “My next trick is impossible!” *Flaring is raising the nose of the helicopter by pulling back on the “cyclic” stick (held in the right hand). It has the effect of raising the nose of the aircraft, reducing the airspeed and, if the left hand holding the “collective” lever is lowered in a coordinated fashion, maintaining height above the ground.

We also did night flying and instrument flying. We would fly circuits at Odiham with only gooseneck paraffin flares as runway markers – rather akin to what is shown in films of the Second World War delivering agents to France. One takes off and climbs away on instruments in total blackness – no mean achievement in a piston-engined Whirlwind where RPM has to be controlled to a precision of 1 or maximum 2 RPM by means of the collective lever and a twist grip throttle at its end. Turning downwind allows one to see, but barely, the goosenecks. One of the most exciting aspects of night flying in a single-engined helicopter is the potential for an engine failure which would inevitably result in a plunge into the blackness! We had Schermuly flares mounted on the undercarriage legs. There were two per aircraft. They were cylindrical and about 18 inches long and contained a magnesium flare and small parachute. In the event of an engine failure, the pilot would establish autorotation (described elsewhere) and then, when ready, fire a flare by pressing a button in the cockpit. The helicopter in autorotation descends at around 1,500 feet per minute at 50 to 70 knots and more at lower or higher airspeeds. The magnesium flare descends on its parachute thus more slowly, the idea being that there is sufficient illumination for the pilot to complete an engine-off landing in safety. Well – it might be possible for a really clever pilot!

In September 1963 there was a large exercise off Dartmouth in Devon. It involved transporting hundreds of VIPs to and from some Royal Navy ships just off the coast. Most of these were Royal Fleet Auxiliaries (RFA’s) with a helicopter platform at the stern. This exercise was shortly followed by an exercise in Libya, North Africa. This is covered in detail later.

Pilot’s notes, the handbook for flying the aircraft, for all marks of Whirlwind was a thin book which gave limited detail. For example, there was no reference to flying in icing conditions. So we just flew in any weather which permitted sight of the ground and examined with curiosity the slivers of ice which dropped off when we stopped the rotors. The Whirlwind Mark 10 arrived with no maximum speed marked on the airspeed indicator and there was no mention in the pilot’s notes. So we flew as fast as we could and, if lightly loaded, cruised at over 100 knots. That is until the manufacturers, Westland Helicopters of Yeovil, got to hear of it. They had a fit, muttering about overstressing the fixed and rotating stars (parts of the rotor head control mechanism) and immediately we had red lines painted at 95 knots on the airspeed indicators.

Social Life

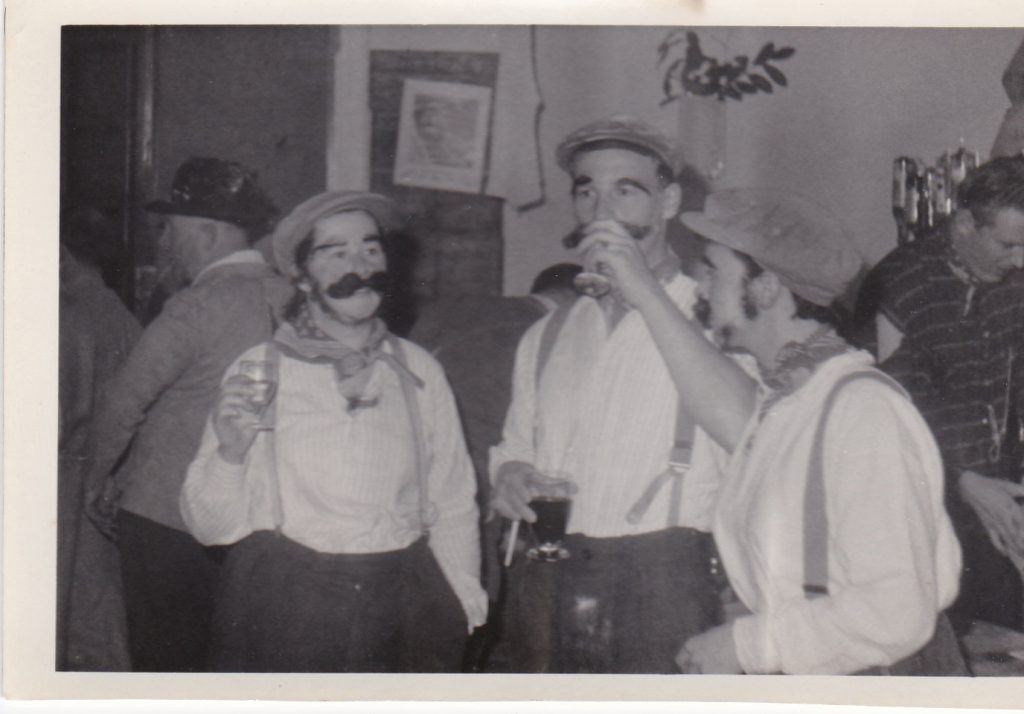

An officer’s mess party during which we were to contribute some small nonsense. The late John and June Barlow and my late wife, Margaret, and I dressed up as road menders and arrived with the wheelbarrow and other kit and set up in the middle of the lounge.

My first engine failure

Retracing a little, in November 1961 No. 225 Squadron was the first unit in the RAF to receive the Whirlwind Mk 10. Instead of the large radial piston engine of the Marks 2 and 4, this Whirlwind had been built by Westland Helicopters with a De Havilland Gnome jet turbine engine* located in the port side of the nose of the aircraft. Not only did it have significantly more power than its predecessors and thus gave a much-improved payload, but also it had a “computer”* to maintain rotor RPM at 220 under all conditions of flight. (*not a computer in today’s sense – just an electronic speed governor receiving signals from some 5 sources such as rotor speed, engine compressor speed, turbine temperature, etc.) The reduction in pilot workload provided by this innovation cannot be fully appreciated unless one has flown both types. On January 16, 1962 I achieved the dubious distinction of being the first pilot in the RAF to have an engine failure on this new type. We were on exercise in Devon and whilst climbing away from a refuel, with the ground densely cluttered with 45-gallon fuel drums, there was a “whoomph” noise at about 20 feet and down we came. All I could do was to rapidly lower the lever and then almost immediately raise it to cushion the touch down in a run on landing (a landing maintaining some forward speed rather than a hover landing). It was then a question of standing on the brakes to come to a halt before hitting any drums. Looking down I was surprised to see my knees oscillating rapidly sideways in different directions. – possibly the result of standing on the brakes and applying incredible force to stop us skidding into the many 45 gallon drums of fuel a few yards ahead. It was a full minute before I regained control of them!

The length of the flame from the exhaust was so long that I could actually glimpse it from the pilot’s seat – which was on the starboard side with the exhaust on the port. There was only one other person on board, a Wing Commander medic who was experiencing his first-ever helicopter flight! All Whirlwind Mark 10 aircraft were grounded immediately. The next day the AOC commanding 38 group and Leo Devine, Westland’s test pilot, climbed into the cockpit and to my amazement were able to start the engine and rotors. I wondered what I had done wrong as they sat there for some five minutes rotors running. They then shut down and told us that they could only get 120 r.p.m. instead of the normal 220. When Rolls Royce dismantled the engine they discovered that many of the small compressor blades had broken off and there was considerable corrosion inside the engine. Although Westland’s had flown this aircraft all around the world on demonstrations, each night it had been put into a hangar. Operations on 225 Squadron had left the aircraft outside in the cold and wet and the compressor blades had suffered from corrosion. The solution, as I recall, was some kind of shellac finish applied to the blades for protection.

*The arrangement on a helicopter can be likened to a turboprop on an aeroplane. The front of the engine consists of an air intake, a rotating axial compressor forcing compressed air into a combustion chamber where kerosene is added to produce a stream of fast-flowing hot air which is directed onto a turbine. The turbine is mounted on a central shaft on which is also mounted the axial compressor. This whole assembly is called the “gas generator” and the residual flow of gas, after passing through the turbine, is then directed onto another turbine (termed the free turbine because it is not connected to the forward rotating assembly of the engine). This turbine is connected to the main rotor gearbox and thence to the main and tail rotors. The computer received signals from a number of sensors, one of which was rotor rpm. The pilot, having selected the speed lever on the central console fully forward, could rely on the computer to maintain the rpm of the main rotor at 220 r.p.m.

Some months later I experienced a computer failure whilst practising landing manoeuvres just off the edge of Odiham airfield. The engine lost power leaving me no option but to continue the landing at reduced power and then climb away back to base using manual* control of the engine. *The Mark 10 Whirlwinds retained the twist grip throttle of the earlier piston engine machines. However, this was only used for the initial start-up and in an emergency should the computer fail. Below 18,000 compressor rpm the engine was in a region wherein any rough movements of the throttle could precipitate an engine stall and a flameout. In order to prevent pilots from allowing the r.p.m. to fall into this region when performing practice autorotations and the like, a flight idle stop was fitted. This stop would be engaged after start-up and left in until preparing for shut down. This modification allowed us to practice autorotations safe in the knowledge that we would not inadvertently stall the engine and precipitate a real engine failure. This matter had an interesting sequel when I was flying for Bristow Helicopters in Iran after I had left the RAF and become a commercial pilot.

An eye-watering experience

On one occasion the squadron departed from our base at Odiham in a VIC* formation and with total low cloud cover. (*Squadron Leader Henry Price and navigator, Jim Sinclair, in the lead ship with the rest of the squadron strung out either side to form a “V”). Now one of the major differences between a formation of aeroplanes and a formation of helicopters is the closing speed should one aircraft get too close to the next aircraft. The closing speed in a formation of aeroplanes would be in the region of a few yards an hour, whereas the closing speed of two sets of main rotor blades is over 800 miles an hour! The potential for utter disaster tends to focus the mind. So our little flotilla of 8 aircraft headed westwards towards the exercise area, which I recall was somewhere in Wales. As is so typical on these occasions, the cloud base steadily descended and so we descended to remain visual with the ground until we were at or below the minimum legal altitude for our positioning flight – 250 feet above the ground or anything fixed to the ground. This is a “really dodgy” situation being fraught with the danger of flying into obstacles such as radio masts or hills. In addition, when flying a single-engine aircraft one has always to remain visual with the ground in case that one engine should malfunction and an autorotative* landing becomes necessary. It is very easy in such conditions to fly into a chunk of even lower cloud and so lose sight of the surface. And, as luck would have it, the aces of 225 squadron suddenly found themselves out of sight of the ground in formation in low cloud with visibility just sufficient to see the next helicopter provided we remained in very tight formation. Our leader, Henry Price, had no choice but to begin a steady climb with the rest of us trying to remain in formation. I don’t know how the others fared but, at a certain point, I lost sight of the aircraft to my starboard, it being between me and the leader. When flying in close formation one is completely focused on the NEXT aircraft and maintaining position relative to that aircraft with but occasional glances at cockpit instruments to check the health of one’s aircraft. To find oneself in cloud in the knowledge that there are seven other helicopters in close proximity but none of them visible to the eyeball is quite an eye-watering experience. I slowly turned 5° to port, away from the invisible helicopter in my 2 o’clock position, and continued the climb in the hope that the aircraft to my port would remain in close formation with me and also turn 5° further to port. After what seemed an eternity the squadron burst into bright sunshine above the cloud layer. It was quite remarkable how close we were to each other yet had all avoided a collision. We resumed formation and continued flying westward until the cloud cover broke and we were able to navigate by visual reference with the ground.

*Autorotation is the helicopter equivalent of gliding. In the event of an engine failure in a single-engine machine, the pilot very quickly lowers the lever (the Collective or Lever) in his left hand as far as it will travel. This has the effect of reducing the pitch of the rotor blades of the main rotor to a minimum. The helicopter will begin a rapid descent of 1500 ft. per minute or more depending upon the airspeed chosen by the pilot. In this condition, instead of the airflow being drawn through the rotor from top to bottom, the airflow now flows up through the rotor. Thus, even though the engine is supplying no power to the rotor gearbox and rotor system, the rotors continue to rotate and, in fact, the pilot must prevent them from overspeeding by judicious use of the collective lever. Although the aircraft is descending rapidly the pilot has directional control and control of the airspeed which is typically maintained at 50 to 70 knots depending upon the type. He manoeuvres the aircraft to arrive pointing into the prevailing wind with a suitable flat and smooth surface ahead, such as a convenient grassy field – if he should be so fortunate! At around 150 feet above the ground he flares (pulls back on the cyclic stick – held in the right hand – thus raising the nose of the aircraft). This results in three positives and no negatives – very unusual in this life! – the rate of descent is reduced, the forward speed is reduced, and the rotor rpm increases providing more rotor energy to cushion the touchdown. At a height of 50 feet (depending on the type of helicopter), the pilot starts raising the collective lever (left hand) and lowers the nose with the cyclic (right hand) to present the aircraft to the ground in a level attitude. Keeping a constant heading by use of the rudder pedals and cyclic, he adjusts the lever to cushion the touchdown, which might be rough if the surface turns out to be something other than smooth grass or tarmac. All this is predicated on the assumption that he has sufficient altitude and airspeed to establish autorotation when the procedure began and there is a suitable landing area to allow a run on landing at 20 to 30 knots, or even less depending on the type of helicopter and the wind speed. This final raising of the Lever is an art form – too early and the aircraft is in a very short-lived state several feet above the ground with a rapidly decaying (reducing RPM and thus reducing lift) rotor speed followed by a very hard and possibly destructive landing – too late in raising the Lever and the aircraft splats into the ground, again with the possibility of destruction!

Secondary Duties

Officers were given secondary duties which were to be performed in addition to their primary roles. Orderly Officer is one such duty which came around on a rota basis and one had the role of visiting the airman’s mess hall and asking whether there were any complaints! As a secondary duty I was given the field kitchen inventory which was located in a locked room in our hangar and contained the equipment and stores necessary to feed the squadron when on exercise. Alan Twigg said this assignment “would teach me a great deal about the RAF”! It did! Flying Officer “William the Naïve” was persuaded by the sergeant cook, the holder of this inventory and due to leave for Cyprus the very next day, to sign for this enormous pile of tinned food, cookers, thermos flasks, plates, knives, forks, spoons, etc. only to learn that there were considerable shortages. It took me over a year to fabricate and falsify documents and claims to bring the inventory up to strength. When a Belvedere crashed after an exercise on the return flight from Germany, tragically killing all on board including a young pilot of 225 Squadron, all of us with inventories seized the opportunity to claim that some of our inventory had been on board. That Belvedere would have weighed more than the Queen Mary!

INCLUDES ALISTAIR MARTIN (he must have something very strong in his coffee!), BILL ASHPOLE, BILL McEACHERN, BARNEY SWINTON-BLAND, HENRY TREVOR PRICE, MIKE GINN

Escape from the SAS

I recall an exercise held on Salisbury plain. The enemy was the SAS. Our Squadron was encamped in a wood with the helicopters parked around the periphery. One night we were awoken by dozens of thunder flashes (like very loud fireworks) going off and much shouting. The SAS had attacked.

We officers each had an Igloo tent – a canvas pyramid supported by a 3D cross of inflated tubes. In the tent next to mine was Stan Lilley. Now one of the problems with exercises is that people can get carried away in their enthusiasm. When an SAS man ripped open the flap to Stan’s tent and shouted for him to get up, Stan decided to whack the intruding head with whatever object came to hand. This appeared to cause some irritation and I heard the guy shout to his mates something about a “****ing nutcase”. There was then a commotion as several SAS guys jumped up and down on Stan’s tent with him inside! This gave me time to put on my gear, including my boots, and, when someone ripped open the flap to my tent, I leapt at the opening, pushing the guy out of the way, and started to run. All around me was noise and commotion. I continued running through the camp, through the wood, and out onto Salisbury plain.

It was a moonlit night. I found myself running up a small hill when suddenly I saw a whole line of men walking slowly towards the wood – a formidable sight. I hugged the ground and kept very still and quiet in the hope that I would not be detected. No such luck! I felt a boot nudge me and heard a command to get up. I was out of breath from my flight from the wood and ask for time to recover. Thirty seconds later I leapt up and made a run for it. To my surprise I was not chased but was left to continue my escape.

It was only then that I noticed an awful smell! I began to realise that this awful smell was coming from my clothes. No wonder that I had not been chased. When the SAS attacked our camp they had knocked over all the chemical toilets and I must have tramped through the resulting mess on my way to freedom.

And that is how I escaped from the SAS!

I waited and listened. The commotion in the wood died down. There was the sound of lorries being driven away – and then silence! I returned to the camp and discovered how eerie it is to be alone when 30 minutes before this had been a hive of activity with over 200 men. Next morning my colleagues were driven back to the camp. They had been dumped somewhere on Salisbury plain. Stan Lilley, a hero to the last, had jumped off the lorry taking them away from the camp and had escaped further capture. He arrived back at the wood several hours after the others, still dressed in his silk pyjamas! n.b see additional comments on this escapade from a 225 Squadron colleague, Alistair Martin, at the end of this section.

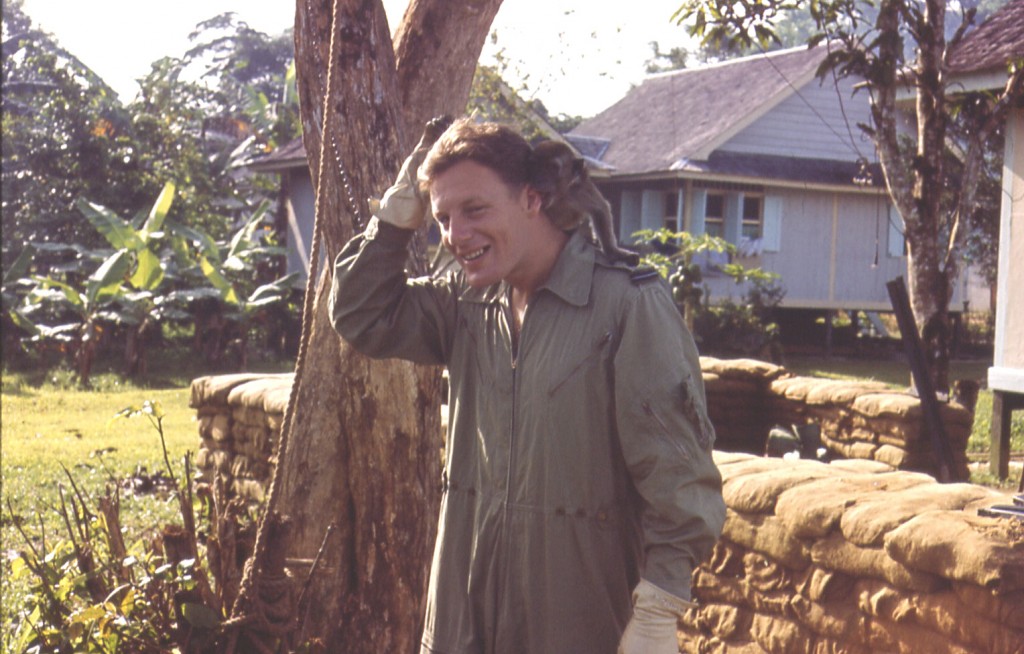

THE CAMPFIRE Top left: Bill Russell walking with John Bleaden sitting. Top right: Alistair Martin sitting with the author standing to the left of the tree and Ted Zuwalski with mug to right of the tree. Front from left to right: Mike Ginn, Bill McEachern, John Barlow, and possibly Stan Lilley. Photo provided by Alistair Martin

An epic positioning flight

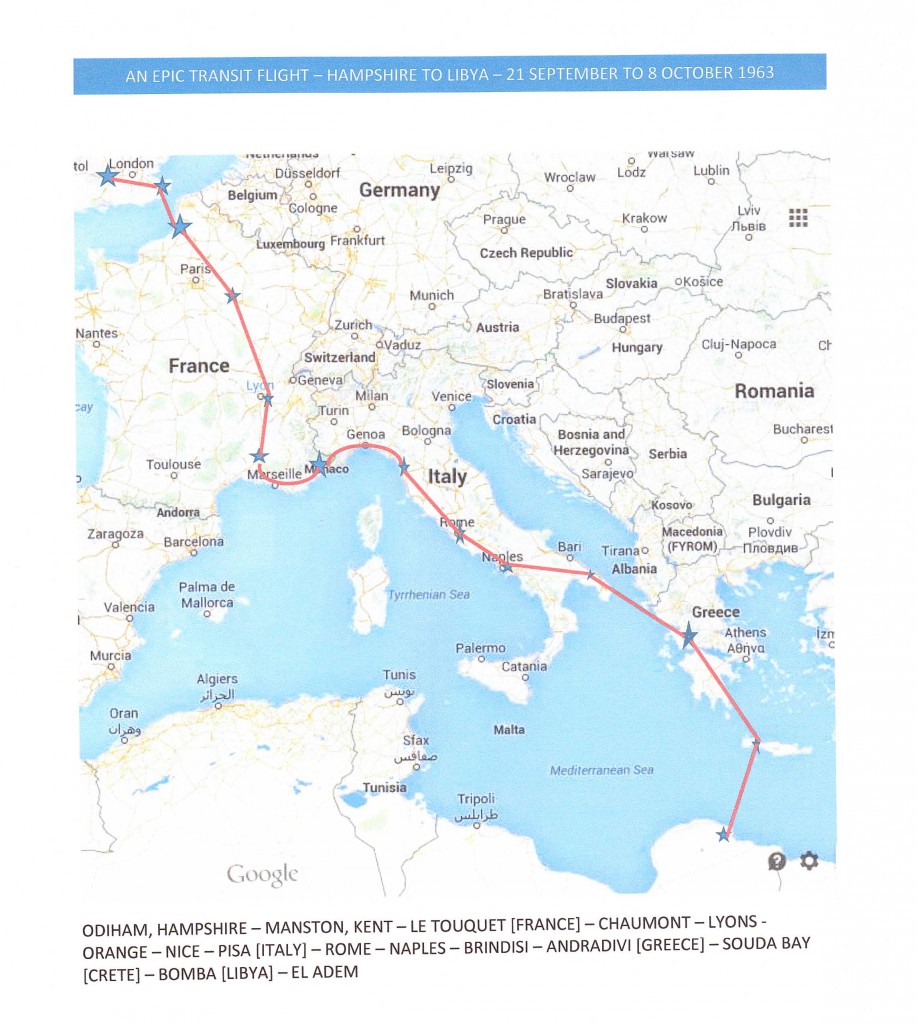

In September 1963, No 225 Squadron and No 22 (Belvedere) Squadron were scheduled to take part in an exercise in Libya, North Africa. Five of our Whirlwinds were disassembled and flown out in Beverley aircraft. Another five were assigned to be flown out under their own steam. Commencing 21st September, Flight Lieutenant John Barlow and I were number three in the five-ship formation which set off from Odiham with destination El Adem in Libya.

We joked about spending a week here and a week there in exotic holiday destinations on the transit flight. Bear in mind this was long before the era of cheap air travel and a visit abroad was still an adventure and a perk. Our joking turned out to be ironical as we were plagued initially with adverse weather and then with appalling aircraft unserviceability. The weather was reliably awful and we crept at low-level from Odiham to Manston and then on to France. We were forced to land in a field somewhere near Le Touquet. The weather showed some signs of improvement and so we climbed back into our machines and started rotors. I will never forget the hilarious radio check-in. “Leader to formation check-in”. “2”… “3”…. “4”… “5 to leader, there is a gendarme here who says we cannot take off”. “Leader to 5, can he stop us?” – “5 to leader, he has a gun”. “Leader to formation shut down”. We eventually got clearance to take off and arrived at Le Touquet. This concluded the first day of our transit flight, 21 September 1963.

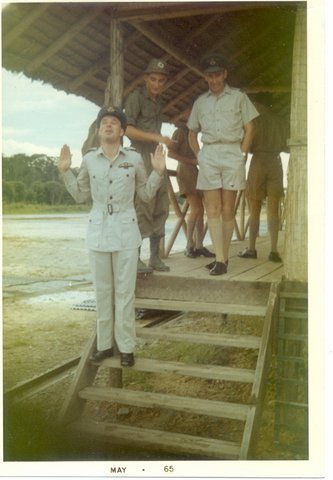

THE AUTHOR WITH JOHN BARLOW AND TOM HOOPER ON THE WAY TO EL ADEM – PHOTO SUPPLIED BY TOM HOOPER (NOTE THE LONG RANGE TANK IN THE CABIN)

The next saga in this epic was our arrival at the top end of the Rhône Valley. The Mistral, a strong wind, blows along that Valley from north to south so should have been in our favour. Our squadron navigator, Jim Sinclair, a lovely man, appeared to have got something wrong! We seem to have been battling into a headwind all the way down to the coast west of Nice. We ran short on fuel and had to drop into the USAF base at Chaumont for fuel and food. My logbook shows that we night stopped at Chaumont. Our next leg was from Chaumont to Lyons then on to Nice. The last part of our leg to Nice was over some hills in the dark without the benefit of Schermuly flares. Our arrival at Nice airport was a shambles involving high hovers searching for a landing pad amongst a collection of parked aircraft. Nevertheless, we all made it down safely. So concluded 23 September 1963.

It was at Nice that Tim Carbis, who was number five in the formation with Group Captain Sheen, station commander of Odiham, decided he had had enough of flying an aircraft with low engine oil pressure and other unserviceabilities. He refused to proceed further on this trek. Other aircraft also had technical problems and it was not until the 26th that we departed for Pisa and then Rome. Whilst waiting at Nice, our support aircraft, two Belvederes, caught up with us. I recall that Bunny Austin was the commander of this flight. To our surprise, they had lunch then departed on their way taking the imprest (funds) with them! The idea that Belvederes could be a support aircraft was rather fanciful. Although Belvederes did perform sterling service in Borneo at a later date, number 22 Squadron at Odiham had suffered terrible unserviceability problems. Their only achievement to date that I can recall was to place the obelisk on the spire of Coventry Cathedral. I hate to think what that operation cost the RAF although I suppose one could put it all down to training. Apparently, Sir Basil Spence, the architect of the spire, had commented that the mock-up obelisk used for practice by 22 Squadron was better than the one he had designed!

On 27 September we departed Rome for Naples. We were stuck there an extra day due to unserviceability but did have the opportunity to test fly and to overfly the crater of Mount Vesuvius. After two more days of unserviceability problems we departed Naples on the 30th for Brindisi at the heel of Italy. Here we almost lost a number of the pilots of 225 Squadron. We were in an overloaded taxi in torrential rain driving along a dockside when one of our number shouted to the taxi driver to turn left. He did so but fortunately realised just in time that we were feet away from the edge of the dockside, obscured due to the deluge.

We were stuck at Brindisi until 6 October due to serviceability and weather problems. In fact, on 3 October we did set off for Andradivi but after 45 minutes were forced to return due to the weather. On 6 October we stopped for fuel at Andradivi and then made it to Souda Bay in Crete. On 7 October we completed the Souda Bay to Bomba sector-2 hours and 45 minutes over the Mediterranean accompanied by a Hastings. On the glorious eighth of October 1963 we arrived at El Adem to coincide with the last day of the exercise. We had avoided days of living under canvas! – Or so we mistakenly thought!

During the exercise a Belvedere had crashed and I was assigned the task of flying a gentleman from the Air Accident Branch, Bertie Morris, to the crash site each day where he poked around among the debris. I did this for 4 days. Upon my return on the last day I was surprised to find that our tented encampment had disappeared together with all the pilots and most of the ground crew. I set off in a Land Rover to discover their whereabouts. I found them eventually in a long queue preparing to board a Britannia bound for England. The Squadron had been given a 12 month unaccompanied tour (single status – no families) to Borneo! I was then told that since I only had eight months to go before my five year short service commission with the RAF would be complete, I was to remain at El Adem, get all the helicopters serviceable, fly them onto the aircraft carrier, HMS Albion, which was due to arrive in three weeks, and then return to the UK where I would remain. I carried out my assignment to which was added a search in the desert for a missing ambulance and the retrieval of a Belvedere gearbox as a slung load. The AOC arrived and asked for my report. Upon hearing that all the helicopters were serviceable he instructed me to send all the ground crew back to England and gave me permission to do the same but return in time to fly the aircraft onto HMS Albion.

Upon arriving back in England I was surprised to learn that although the Transport Command operations order had not included my name, my squadron commander had added it. If I had not returned to England I would, doubtless, have not seen my pregnant wife at all!

My last flight at El Adem was on 16 October 1962.

Brief background to the Borneo campaign

Malaya received its independence and became known as The Federation of Malaysia consisting of the large mainland peninsula plus the island of Singapore plus the states of Sarawak and Sabah, these latter two being contiguous with Indonesia. The President of Indonesia, by the name of Sukarno, had other ideas and decided he would annexe Sarawak and Sabah and progress to taking over the rest of the Federation as well as the Philippines! The Malaysian government called upon Britain to protect their interests – quite a task with some 210,000 square miles of former British North Borneo with a border of 1,000 miles separating it from Indonesian Kalimantan.

Departure for active

The Squadron was bussed to Stansted airport at the beginning of November 1963 for the pleasure of a grinding 30 hours in a Britannia operated by the airline British Eagle! The sights and smells of the Singapore of that era were quite an experience. HMS Albion arrived and on 20 November we flew the helicopters to RAF Seletar. There we were spared the three-day jungle survival course to spend only a few hours trekking. Over the next few days we flew to Kuala Lumpur and Butterworth and did some jungle clearing exercises where we learned how to climb out over 200 foot trees without killing ourselves. There was an amusing incident concerning leeches. All but one of the pilots were a bit casual concerning lacing up the jungle boots which the RAF had provided. But one of our number, George Warren, had been fastidious lacing up every hook. Disrobing in the crew room afterwards George gave a cry when he discovered leeches had penetrated his armour! The rest of us were unscathed.

A rather bizarre incident took place at Seletar. The AOC (Air Officer Commanding) was due to arrive to review the troops. All personnel from the newly arrived squadrons were on parade ready for the inspection. A Belvedere , immediately adjacent to the parade, commenced its starting routine, fortunately without the co-pilot present in his seat. Thanks to the fact that the Belevedere had been produced to a Royal Navy requirement*, it had an explosive cartridge as part of its starting mechanism. It exploded and a fire began! The ground staff cheered! Now some genius had positioned all the station’s fire engines at the opposite end of the airfield to the helicopters. It took some time for them to arrive. At first, not one of the engines produced any foam. The fire intensified! Then one engine started to produce foam but this was promptly curtailed when another engine ran over the hose! The fiasco continued until the front rotor blades began to droop and eventually the front of the aircraft was a molten blob – a CAT 5 write off instead of a minor fire!

On 8 December we departed Seletar for HMS Albion and after a three-day cruise arrived in Kuching. All the squadron aircraft arrived in formation except for one which took a more circuitous route since it was stacked high with Royal Navy grog! On 14 December 1963 No. 225 Squadron began operations for real in the Borneo confrontation. We were issued with a Browning semi-automatic pistol and a Sterling sub-machine gun. The pistol was worn on a belt around our waist and the Sterling was laid on top of the instrument panel. Occasionally, one of our squadron RAF Regiment guys would be set up in the cabin with a Bren gun pointing through one of the window apertures. The device was equipped with a metal strip to reduce the possibility of him shooting the tail or main rotor. All of this was in marked contrast to the helicopters being used at the same time in a different theatre, Vietnam, by the various air forces of the United States.

‘Ere be dragons

We were given a briefing on the situation obtaining in Borneo and were issued with maps which bore the motive “ere be dragons”, the mapmakers sign that information is not reliable. There was a dotted line on the map to show the border between Borneo and Indonesia. In the real World the terrain was a carpet of trees or scrub with the occasional hillock or hill and the actual border was very hard to identify.

There was a detachment of two Royal Navy Wessex aircraft already based at Kuching airport, commanded by Lieutenant Geoffrey Atkins. He volunteered to show us around the local area but this kind offer was rejected! – arguably, not the wisest of decisions! In this small World I was to meet up with Geoffrey many years later with British Airways Helicopters at Penzance. On the first day of operations the pilots of 225 Squadron were assigned, two in each aircraft, to fly around the local area and gain experience of the terrain. An Army Air Corps pilot in an Auster reported that he saw a Whirlwind cross the border at 90° and proceed into Indonesian territory. As he watched he saw the helicopter suddenly turn violently and head back across the border. It landed shortly after at a helicopter pad. The pilots, John Bleaden and Brian Danger, were unhurt but the aircraft had suffered five bullet holes, one of which had hit the unit which added up the contents in the various fuel tanks giving the pilots a zero fuel indication. The helicopter was quickly repaired and put back into service. We heard that the terrorist responsible had been subsequently caught. Apparently he had heard the helicopter approaching, had raised his machine gun, and fired on an opportunity basis at the helicopter!

This was the only hostile experience that we recorded during my eight months spent in Borneo. There was another incident, rather amusing, when Ted Mallett-Warden, a Royal Navy lieutenant seconded to 225, landed and spotted a bullet size hole in his aircraft. We gathered around him offering our congratulations at his lucky escape when one of our chief technicians arrived and said “before you gentlemen get too excited, we drilled that hole to stop a crack spreading and this is the airman who did the work!”

Living accommodation

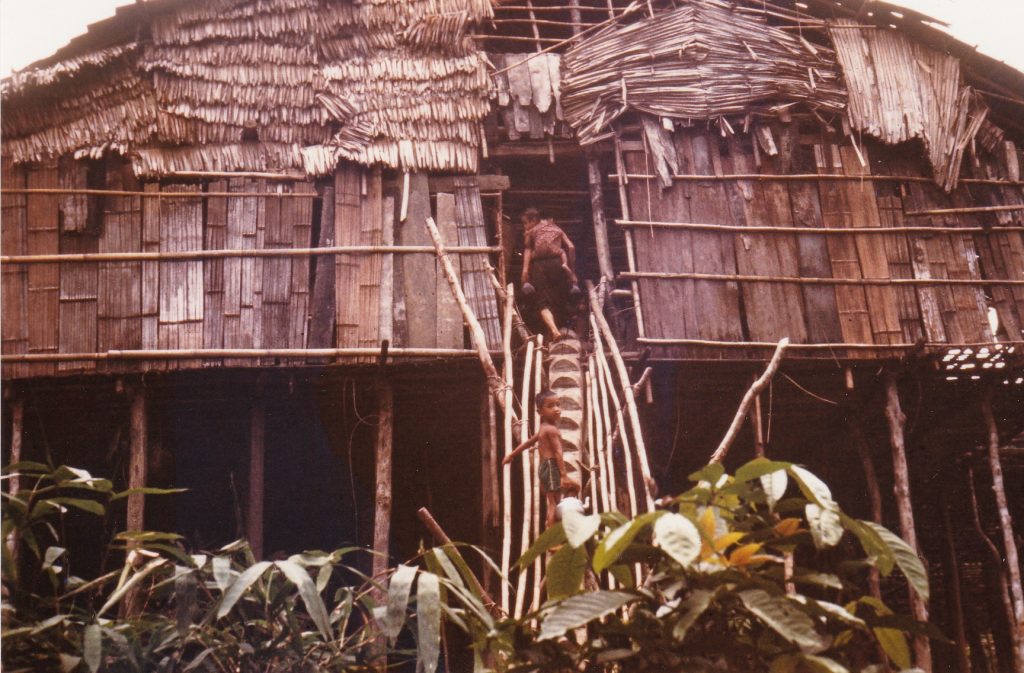

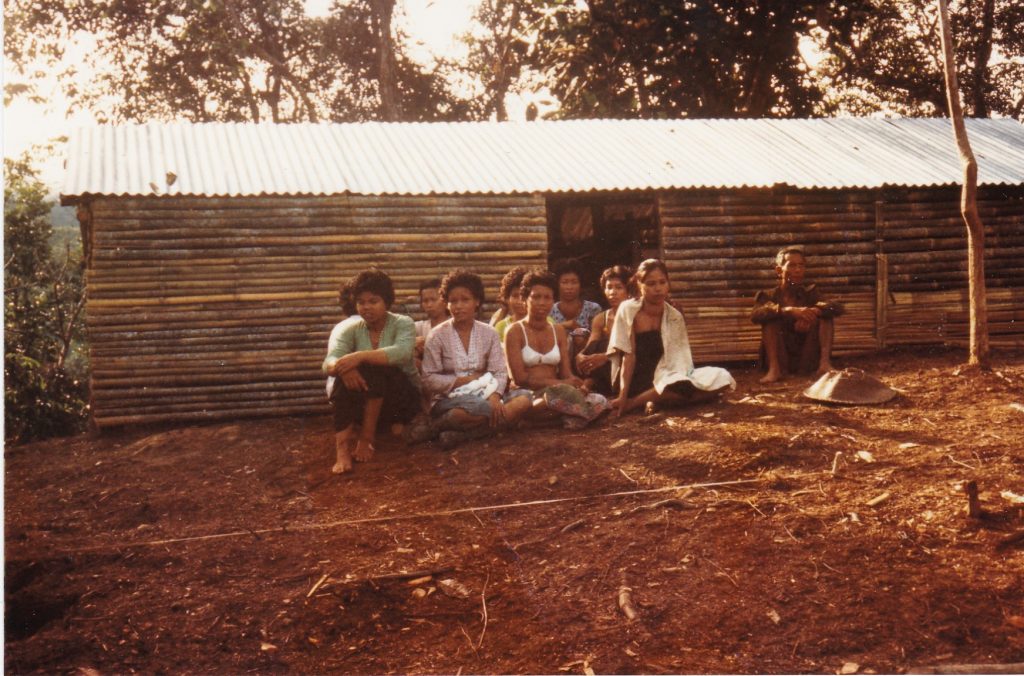

Accommodation at Kuching airport was, at the time, very limited and much was under construction. The half dozen flying officers were billeted in the nearby mental hospital in a rather nice bungalow. Presumably, someone had considered the security aspect? One of the local medical staff who lived closest to our bungalow was extremely friendly and we had many invites to his house to partake of sumptuous Chinese meals always eaten in a hail of insects – a fundamental part of life in Borneo. Apart from eating in the officer’s mess at Kuching airport, we would also go into Kuching town where there was a rather nice club with a swimming pool and also several Chinese restaurants which offered excellent food if one could stomach passing the toilets on the ground floor before ascending the stairs to the dining room. A few months after our arrival we moved into the officer’s mess on Kuching airfield. The camp was entirely of “bashers” – sheds constructed of wood and leaf.

At Simanggang, which was one of the two detachments from Kuching along with Lundu, the Royal Engineers had drained a swamp and built “basher” type accommodation on the site. It was unusual to see snakes but one individual was sitting on the throne one day and looking up saw a large snake coiled above his head. Quickly despatched by a native cook, the unfortunate animal ended up as soup. Insects were everywhere and after watching a film in the mess, the parachute stretched over the audience would be heaving with every kind of bug. Rats were also prevalent and after being nipped whilst asleep one night I decided to “rat proof” my room. This was done by tacking used supply parachutes around the room to achieve a complete seal except for the door. It kept out the rats and insects but kept in the air. The temperature was extremely unpleasant but since we lived in a permanent state of sweat, one got used to it. We did not have electric fans.

BORNEO – JUNGLE AND MOUNTAINOUS TERRAIN – VERY UNFORGIVING IN THE EVENT OF AN ENGINE FAILURE! (PHOTO WIKIPEDIA)

We arrived in Borneo in our blue UK flying suits which were totally unsuitable for the heat and humidity of the Far East. We managed to scrounge suits from the Australian Air Force. These were made from much thinner material. After laundering they were clean and fresh but after only a few minutes of wear they were soaking wet with sweat.

Flying operations

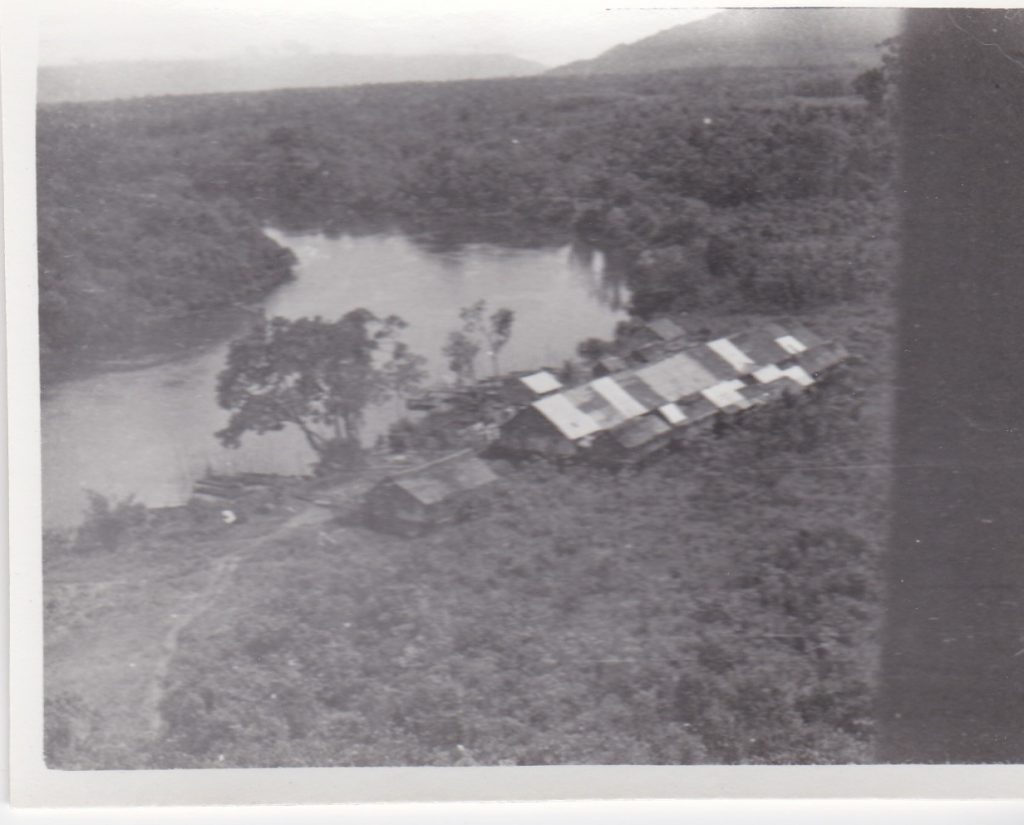

Operations for 225 were based at Kuching airport and also Lundu and Simanggang. We supported various regiments including the Ghurkhas and the Marines. Whatever was wanted, 225 delivered.

KUCHING – ONE OF THE AIRCRAFT OF 225 SQUADRON IN UNITED NATIONS THAILAND MARKINGS FOR THE TRUCE TEAM; LEFT TO RIGHT – IAN RICHARDSON, ALEC TARWID, TOM HOOPER, JOHN BARLOW & RON KING – PHOTO SUPPLIED BY TOM HOOPER

My logbook records a press visit on 30 March 1964 and by a Japanese TV team on 9 April. On 17 and 18th June the Thai verification team, part of the peace process, needed airlifts. Three of our aircraft were whitewashed and large UN letters were painted on the side. I recall landing, with two other helicopters, to pick up the team. When I tried to start my engine, nothing happened. So in front of the world’s press I climbed down the side, opened the electronics bay cowling, and gave the starter solenoid box and hefty whack. I then climbed back up, the engine started and we went on our way.

Flying operations were in general routine with the occasional very challenging assignment. I recall one very interesting incident out in the deep jungle in the Simanggang area. Because of the very poor maps, Hunting Aerial Surveys were engaged by the Ministry of Defence to improve the situation. They would fly over the region on very clear days and photograph the terrain using a double camera which could produce 3-D photographs of the whole area which were then made into topographical maps. The next step in the process was to precisely determine the spot heights of various places in order that contours could be added to the maps. We would fly along with a three-man team of cartographers who would direct us to a precise location where they needed a spot height. It was rarely possible to land at these locations and so we had to find a nearby suitable touchdown point. Rivers with sandbanks were often ideal for this. On one occasion I landed and the team departed into the jungle to climb a nearby hill whilst I sat rotors running awaiting their return. Suddenly, out of the dense jungle appeared some 20 pygmies. They were naked except for black loincloths. Each had a snake tattoo on his torso extending from neck to loin cloth. Each also had a spear! I sat there helplessly hoping that they were friendly and not head-hunters. Then, in a flash, they all ran under the rotor towards the open cabin door of the helicopter. It did cross my mind that I might soon be feeling the odd spear jabbing my legs and other parts! Looking down towards them from my seat in the cockpit I could see they were all standing around the door jabbering and clutching each other, clearly frightened. Their curiosity satisfied they, to a man, suddenly rushed away from the helicopter and back into the jungle. Naturally, I breathed a great sigh of relief. The team returned and climbed aboard. I then had the challenge of climbing away in this very hot and humid environment. In these conditions a helicopter pilot has the difficult task of moving off from the hover*. I recall that this river had a 90° bend and so I was scraping for lift and having to turn at a critical point before, mercifully, we began the climb! All in a day’s work!

PIGMY – ALMOST NAKED – WITH BLOWPIPE – VERY SIMILAR IN APPEARANCE TO THE CROWD WHO VISITED ME ON THE RIVER BANK (PHOTO WIKIPEDIA)

*A helicopter requires a lot of power to hover. This requirement for power reduces to a minimum at around 50 knots for the Whirlwind then begins to increase as speed increases to the maximum speed permissible, typically around 100 to 130 knots for the older type of helicopter and around 90 for the Whirlwind Mark 10 in hot climates. In a low hover, (less than one rotor diameter), a cushion of air builds up under the rotor and the hover can be maintained at a slightly reduced power than for a “free air” hover. However, as the pilot tries to move forward, backwards or sideways, the ground cushion effect reduces – it is rather like standing on a slippery hemisphere – and unless more power is applied, the helicopter will descend. But, paradoxically, as airspeed increases less power is required to maintain height above the ground – the so-called “translational lift” effect. So the pilot passes through a critical phase when loss of ground cushion effect has to be replaced by translational lift. This is not a problem if the aircraft has ample power reserves but in the very limiting conditions described above, it can be extremely hazardous!

Working with a troop of Ghurkhas. Living with these fierce and loyal fighters in the jungle was a privilege and an experience, especially at meal times. They ate curry for all three meals of the day – a bit on the rough side for breakfast!

On another occasion when based at Lundu, we were tasked with collecting an object some miles away in the jungle. A decision was made to lift the load on the winch cable. The pilot flying, not me on this occasion, established a hover in the very small clearing surrounded by bamboo trees. Wisdom dictates that when performing a lifting operation with a helicopter which does not have an ample reserve of power, the technique is to raise the Collective Lever* in order to commence the climb. (*This is a large lever held in the left hand and movement up or down increases or decreases respectively the pitch of all main rotor blades by an equal amount thus increasing or decreasing the lift force). However, instead of lifting the load by means of rotor power, the pilot handling the controls on this occasion (name omitted to protect dignity) began to operate the winch to lift the object. He must have allowed the aircraft to move forward a few feet as, sitting in the left-hand seat, I could see the bamboo trees around the clearing getting shorter and shorter as the rotor blades hacked their way enlarging the clearing! We did eventually get the load back to Lundu but at the cost of three rotor blade tips and a considerable loss of pride. All this goes to show the very limited power we had in spite of having the benefits of a jet engine.

Beyond eye-watering

A truly frightening episode took place during a night flight from Simanggang by Tom Hooper and Eddy Forsyth. They were tasked with taking a soldier, who had accidentally shot himself, to hospital in Kuching. In the darkness they inadvertently flew into the lower levels of a cumulo-nimbus cloud. Due to the extreme temperatures and the high humidity in Borneo, these could develop vertically for thousands of feet and be accompanied by tremendous thunderstorms. One of the essential features of such clouds is the huge up and down currents of air within the cloud. Tom and Eddy found themselves ascending at an alarming rate BUT WITH THE LEVER FULLY DOWN! Now whereas in a glider it might be advantageous and fun to be carried upwards by a thermal in good visibility, it is an altogether different experience to be doing the helicopter equivalent of “gliding” in the pitch black of a Borneo night illuminated by only the occasional flash of lightning! Our two heroes finally abandoned their mission and turned 180 degrees to escape their fate. They were extremely fortunate and succeeded in exiting the cloud and returned to Simangang. They recovered as did the soldier.

A duel

I was very familiar with firearms having been a target shooter since the CCF at grammar school. During flying training in 1960, whilst in a service competition at Bisley, I won a place in the RAF Rifle 100 and also the Sub-machine-gun 50. An interesting episode took place in Simanggang working with the Ghurkhas. The Ghurkhas had British commissioned and non-commissioned officers. One meal time, a British sergeant pointed at my Browning pistol and made derisory comments about the ability of the RAF as regards the use of firearms. The game was on! We met in a cutting in the jungle where the Ghurkhas had constructed a 25 yard range. The sergeant and I duelled using paper targets and not each other! We were surrounded by a whole company of these brave and ferocious brown soldiers. The honour of the RAF was upheld that day, but only just, and he had to buy the crate of beer for all the intensely interested spectators!

KUCHING – THIS BIZARRE SCENE FEATURING TOM HOOPER AS AN OBJECT OF ADULATION – THE MAKESHIFT STEPS WERE FOR USE WHEN CARRYING VIP’S – SOME OF WHOM HAD DIFFICULTY STEPPING UP TO THE CABIN SILL – PHOTO SUPPLIED BY TOM HOOPER

A near death experience

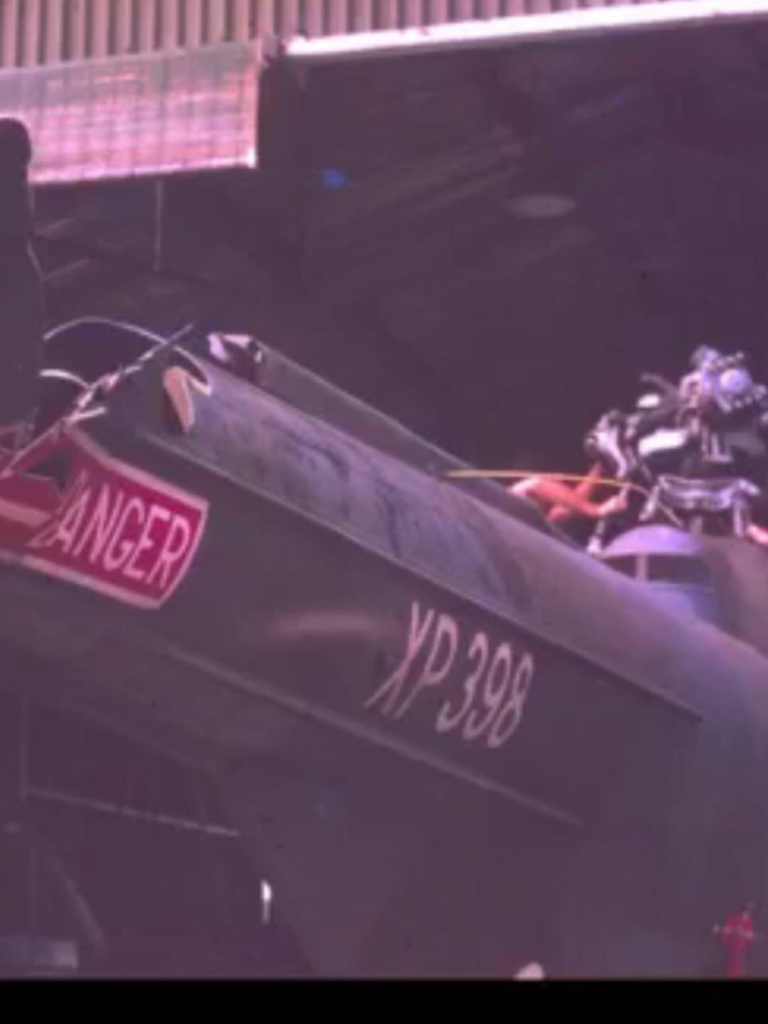

On one occasion I was asked to carry out an air test following some maintenance on one of the helicopters. I took off from Kuching, carried out the usual airborne checks and, being satisfied, returned to our dispersal for the landing. I touched down and retarded the speed selector lever to allow the rotors to stop. A mechanic approached and stood just outside the rotor disc. I applied the rotor brake and immediately after the rotors ceased rotation a look of horror appeared on his face. He pointed in the direction of the tail rotor and shouted a few expletives. I climbed down from the cockpit to see what had caused such alarm. The photograph is self-explanatory.

The strength of the tail rotor, as for the main rotor, lies in the aluminium “D” section of the aerofoil of each blade. The rest of the rotor blade is just streamlining, relatively thin metal covering a honeycomb. The photograph shows that the “D” section was cracked along at least one half of its total circumference. It is, of course, pure conjecture when exactly this occurred but, apart from some angelic ministration, it could only have commenced a few seconds before touchdown. The tail rotor on the Gnome Whirlwind revolves at 1015 revolutions per minute. The centrifugal force acting on each of the two blades is substantial and a blade in such condition could not have lasted more than a few seconds before separation would have occurred. If that section of the blade outboard of the crack had separated from the tail rotor, the out of balance forces on the tail pylon, the vertical fin protruding upwards from the rear fuselage on which the tail rotor is mounted, would have ripped the whole tail pylon from the aircraft. There had been a previous case on an earlier version of the Whirlwind and the resulting massive forward movement of the centre of gravity had doomed the unfortunate pilot to descend rapidly in uncontrolled flight into the ground.

Some members of 225 squadron relaxing in the Sarawak Club in Kuching. Characters include George Warren, Cliff Paice, John Barlow.

A brief vacation

In February 1964, my wife was due to give birth to our second child, a boy. Sadly the first, a girl, had died an hour after birth a couple of years earlier in the Louise Margaret military hospital in Aldershot. I had considerable support from my fellow officers in getting me back for the second birth. At one point, following orders, I had actually put my kit aboard a Bristol Freighter ready to fly to Singapore. Unfortunately, the station commander saw me carrying a clearance chit and immediately cancelled the move crying that he needed every helicopter pilot. A few days later the squadron had a visit from what might be termed the personnel branch of the RAF. The movement order was issued again and I returned to England to be present for the birth. After six weeks I was on my way back again to Borneo, this time in a Caledonian Airways DC7 from Gatwick. I had no idea then that one day I would be employed by the successor to Caledonian Airways, British Caledonian Airways and at Gatwick.

My last flight in Borneo was an air test on 13 July 1964 after which I returned to Singapore and then back to England by RAF Comet. My RAF short service commission terminated at the beginning of September 1964 after which I entered the commercial world of helicopter flying.

Epilogue to my time with 225 Squadron

I look back on my days with 225 with affection and pride. We always carried out our flying tasks with determination and professionalism. We pioneered many aspects of helicopter operations and it is gratifying to watch newsreels of RAF helicopter operations in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere in the World knowing that we played our part in establishing good practice and expanding the envelope of the possible even though our machines and aids were very crude compared with today’s equipment.

I recommend to any reader a book with the title “Borneo Boys” – RAF Helicopter Pilots in Action – Indonesian Confrontation 1962-66. Written by Roger Annett and published by Pen & Sword Aviation Books. This very interesting and well researched volume takes the story of No 225 Squadron more or less from the time I left to its disbandment with the role then taken over by other squadrons until the end of the conflict. Another book which is an excellent read is “More lives then a cat – Flying Tales of the Unexpected” – by Trevor Price who was my squadron commander for most of my time on 225. This book reviews his interesting history with the RAF including his battles with a sometimes indifferent hierarchy in an unrecognised war. It is produced by Past Historic, Kings Stanley, Gloucestershire and contains some very complimentary letters from commanding officers of 40 and 42 Commando and one from the Air Officer Comanding 38 Group, all of which praise the support given by 225 Squadron in Borneo.

The following two photographs were kindly sent by Dennis (Des) Collins who served with 225 after I left Borneo. I have included some notes from Des at the end of this section.

Simanggang – awaiting the arrival of Air Commodore Sir Augustus Walker AOC Far Eastern Command. Detachment commander Flt Lt John Reynell with hands raised, Des Collins in jungle greens and Brendan Spikins

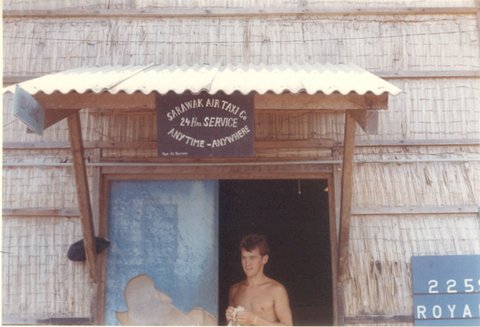

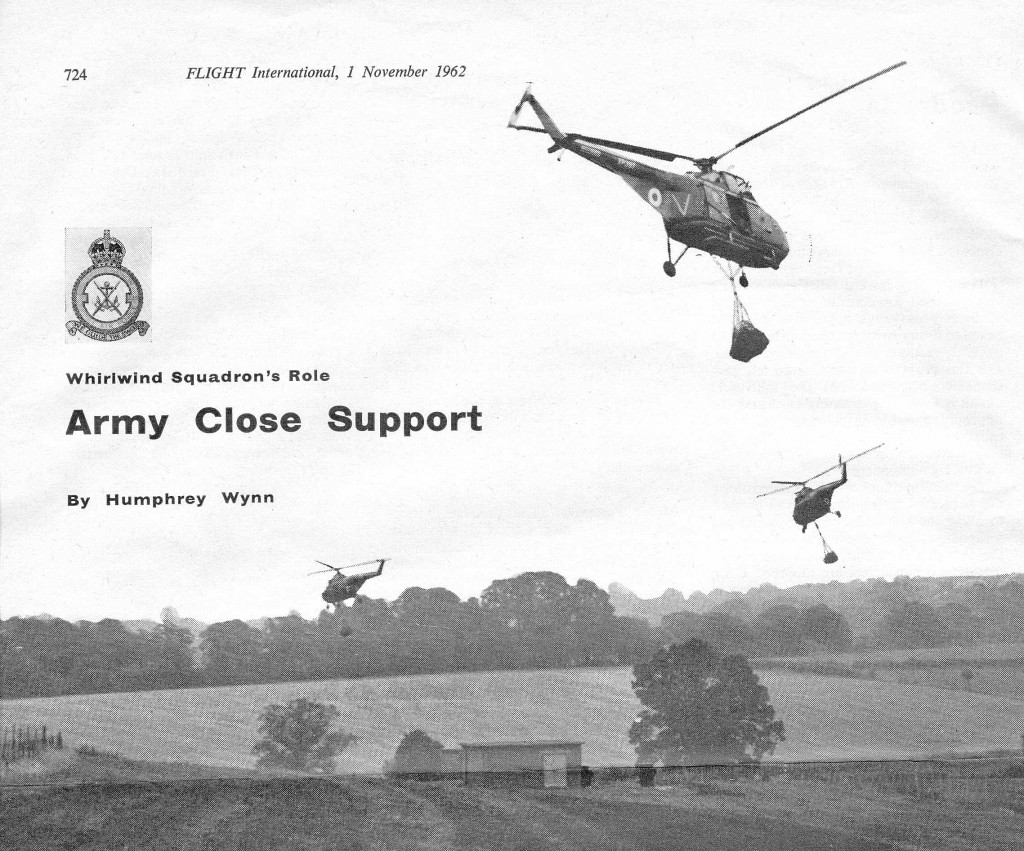

Article by FLIGHT International, 1 November 1962

PINNED to the wall in the 225 Squadron crew-room at RAF Odiham is a City of London flag, the familiar red cross on a white ground, with a sword in the top left-hand corner. Attached to this flag is a note stating that it was presented to the squadron in recognition of 225’s part in the Lord Mayor’s Show last year, when the unit’s Whirlwinds airlifted men from the RAF Regiment on to barges moored in the Thames.

This symbol of the squadron’s participation in city pageantry might be paralleled in many different ways to symbolize 225’s operational activities, such as airlifting supplies for the Army; casualty evacuation; missile- and gun-firing; minelaying; training parachute troops; assisting flood victims; spraying mosquito-ridden ground; and carrying VIPs. In fact, there seems to be no helicopter role which 225 has not tried; and this is hardly surprising when it is recalled that the present squadron was formed (at the beginning of 1960) from the Joint Experimental Helicopter Unit. A good deal of experimental work is still undertaken, particularly with weapons, like Nord SS-11 anti-tank missiles; but 225’s regular task is to support the Army, as part of the short-range tactical transport force controlled by 38 Group, and in/this activity it has a reputation based on historic status as an Army Co-operation unit.

Although the original 225 Sqn was formed in 1918 it had scarcely any operational history in the First World War, its real existence beginning in October 1939.

Odiham was the squadron’s first station in the Second World War, during which 225 operated Hurricanes, Mustangs and subsequently Spitfires. Initially the unit had a variety of roles but mostly its activities had an Army co-operation flavour: photographic, artillery and tactical reconnaissance; lighter-bomber operations.

It wasn’t until the autumn of 1942 that 225 really got into the thick of the air war, when sent to North Africa to join the Desert Air Force. The story of those days has been told in a book published last year under the title The Unseen Eye1. Its author is the Commandant of the Central Fighter Establishment, Air Cdre E. G. L. Millington, who commanded 225 in north-west Africa and up to the Salerno landing. The squadron subsequently supported the invasion of Occupied Europe and after hostilities ended went to Austria with 2nd Tactical Air Force, being disbanded in 1947 in Italy. The squadron’s motto, “We Guide the Sword,” carries for posterity an echo of wartime PR days.

Nowadays, 225 co-operates even more closely with the Army (“we work with the Army, not with the RAF,” says the CO, Sqn Ldr H. T. Price), but transports—rather than guides—the sword. The unit operates in support of Britain’s Strategic Reserve and is ready to go at a moment’s notice to trouble-spots anywhere in the world.

After becoming a helicopter unit—revival of the squadron coinciding with the re-creation of 38 Group—225 operated Sycamores and piston-engined Whirlwinds. Now, however, they operate turbine-powered (Bristol Siddeley Gnome) Westland Whirlwind Mk 10s. This aircraft has several advantages over its piston-engined predecessor: greater lifting power, enabling the carriage of seven or eight soldiers; computer control of engine and rotor r.p.m., so relieving the pilot of hand throttle adjustments when altering collective pitch (an advantage for pilots trying to map-read while operating at about 10ft); increased confidence when flying at low level; and reduced engine noise. The low noise-level is not only comforting inside the aircraft but an important asset tactically. As far as maintenance is concerned, the squadron are pleased with the compact and accessible Gnome installation. At present. 200hr flying can be done between minor inspections.

Pilot Adaptability

In operations with the Army in the field (which is where 225 spend most of their time) concealment from view is sought wherever possible. Maintenance is carried out in the open air, and all pilots are qualified in servicing. Their adaptability is stressed by the squadron commander when he says: “Every pilot has to be an individual.”

Assignments are extremely varied: picking up a casualty arriving by air at Northolt, to take him to hospital; participating with the Army in exercises or taking part in demonstrations for Royalty or Service chiefs, as last Friday when the Duke of Gloucester visited Odiham to present a Standard to 230 Sqn.

Behind all these operations lies the core of 225 Sqn activities: self-sufficiency among the pilots, and in the squadron as a whole; and close co-operation with the Army. Sqn Ldr Price emphasizes that when a pilot is given a job to do, it’s entirely up to him how he plans and executes it; while as to materiel self-sufficiency, the squadron is completely equipped to look after itself in the field, with its own cooks and bottle washers, MT drivers, telephonists, etc. There is a high degree of operational integration with the Army. The unit wear Army-style combat kit, live under canvas during exercises, and try to avoid taking their aircraft back to an airfield if serviceability can be achieved by temporary cannibalization. On the squadron are 18 members of the RAF Regiment, who act as loaders and despatchers. It is these men who guide the pilot when he picks up troops or a load, wearing bone domes and plugged-in to the aircraft’s RT by external lead. In the field, the squadron relies on the Army for fuel. Usually it comes in 45gal drums and is transferred to the Whirlwinds through pumps carried in Land Rover trailers.

Perhaps the best kind of symbol of 225’s activities would be a map of Europe and Africa, for during the past 18 months the squadron have operated in Germany, France, Libya, Kenya, Somalia and Greece, as well as all over the United Kingdom. They are liable to be in any NATO exercise in which the British Army is participating, and may be called on to assist in any emergency. When in the field, they live hard; and they are subject to sudden attacks by Special Air Service forces (with whom socially they are on the best of terms).

All this adds up to a squadron in which personal initiative plays a tremendous part, making present 225 members worthy successors of their wartime Mustang and Spitfire predecessors.

- Anthony Gibbs Phillips Ltd. 16s.

I am indebted for the following contribution submitted by Des Collins and refers to a period after my departure from Borneo

I arrived in Kuching late in 1964, I’d had a bad “first love” relationship whilst serving at 32 MU St. Athan and trying to escape I volunteered for the biggest hotspots of the time. Cyprus, Aden and Borneo (didn’t even know where the last was at the time).

Of course the Air Ministry knew better and decided that they needed more volunteers for Borneo than any of the other two scenarios. At 19 years old I didn’t realise the risk I was taking (the basis of every recruitment program since Caesar or earlier). In hindsight I’ve never regretted the decision I made, it formed me and in comparison with the majority of “cannon fodder” in history I not only had an enjoyable time I learned many important lessons of life at a very early age, and survived.

Much of this can be attributed to the people with whom I worked with on 225 squadron. Not only my direct comrades but especially the (what we would now call management). Officers and NCO’s that understood the positive potential of leadership by example as opposed to position. This was really brought home to me when being detached to the 1e 10th Gurkha Rifles at Simmanggang. If you’ve ever worked with the Gurkha then you understand what I mean. Their respect is not earned with rank or position but with whom you are within their definition of what is worthwhile.

The respect that our pilots earned was similar. I can’t think of any officer or NCO that in my time with 225 needed to fall back on his rank.

I’d only been at Kuching a couple of days and was assigned to doing something electrical on wire guided missiles mounted on one of our helicopters. Not knowing what I was actually doing and therefore following instructions I assisted without burning anything except the back of my alabaster knees. This caused me to perform a bad impression of the goose stepping enemy of WW2 for the next week. I was advised against reporting sick as this could be construed as a self inflected injury resulting in an even worse retaliation from the powers that be.

After the first two months at Kuching I was informed by the engineering officer that I was going up to Simmanggang because the corporal electrician was being repatriated and his replacement, much to the chagrin of the engineering officer, had absolutely no helicopter experience. I was told just to take what I would need for a couple of weeks while they trained the newcomer. I was instructed to leave the rest of my kit in my lockers at Kuching. I was of coarse more than delighted – hey Simmanggang or Lundu were for ground crew the icing on the cake. Even if only for a couple of weeks I was going to enjoy this to the full.

Whatever the reason I don’t know and at the time never wanted to (let sleeping dogs etc.), only at the end I had to request my own return to Kuching pending my own repatriation date.

During my stay at Simmanggang a number of moments became impressed if somewhat disconnected in my memory banks. Toward the end of my detachment the visit of “Gus” Walker was a memorable moment. Knowing of his impending arrival we were set to cleaning anything that remained still for more than 30 seconds. Obviously our pride and joy were our three WW mk10s. Anybody ever having to present a bulled up mk10 recognises the positive effect of “Cherrying”. This involves after washing the airframe rubbing it in with hydraulic oil which is a cherry red in colour hence the term. Some say this also had a protective effect in a saline rich environment (didn’t see much salt water at Simmanggang). However we had a certain lack of hydraulic fluid at Simmanggang so that only the visible side was treated. This resulted in very strange apparitions flying around the area in the following days.

Then there was the day that for a calibration check a mk10 was defueled and to effect this properly the aircraft had to be brought under a (if I remember correctly) 3° tail down attitude. Fortunately our dispersal had the necessary declination. Therefore just push the aircraft back enough to make use of the natural slope. Unfortunately a radio technician was put on the brakes and he was not aware that he was required to pump up the hydraulics to make the brakes effective. The result was that the unfortunate helicopter continued to roll until it came to rest in soggy ground behind the displacement. This resulted in the longest and most protracted recovery in aviation history at Simmanggang.

The local civil engineer suggested building an improvised raft from 40 gallon drums after which he would flood the morass so as to float her out. This idea was treated to the (dis)respect it deserved. The REMY with their recovery crane discovered that their boom was too short (a great disappointment for the macho army bods). In the end Mr. Spikins[1] decided, apparently contrary to all the regulations to fly her out. This he did, even if very gingerly, in what was probably the shortest flight in time and distance that he had ever performed. Probably never even having been entered into the Form 700.

Then there was the sub detachment to Jambu, a hill position on the border where a company of the Gurkhas were stationed with a small detachment of the Malay army with a 105mm howitzer. 225 were flying so regularly with everything except perhaps the kitchen sink that some clever strategist suggested placing two ground crew on the hill (two week rotation). This would increase the load capabilities when flying between Simmanggang and the Hill. This worked really well and I was one of the lucky ones suitably expendable to be sent up to the Hill. Together with a RAF regiment lad we spent regular tours away from the maddening crowd. At the same time being protected in our little hole under the ground by the best little fighters on this world. If they were not enough there were regular visits from the Iban border patrol that really seemed to be in symbiosis with the Ghurkhas.

Here I had my first experience eating a true Ghurkha curry. I was very sceptical at trying this and only agreed if I was allowed to cook something British that they would eat. The quartermaster agreed and the festivities commenced with the drinking of some of the strongest rum I’ve ever drunk. After one or three cups the first curry dish was presented. I believe it was delicious. Maybe the rum was having more effect than I realised. Then it was my turn and the only thing I could come up with at the time was fried egg and chips, except we had no potatoes. Have you ever tried to eat a fried egg with your hands (the Gurkha way of eating) – after licking egg yolk from my arm up to my elbow I decided that I needed another mess tin of their rum before retiring to my little hobbit hole.

On the Hill or at least in the vicinity thereof were regular airdrops. It was then the task of our helicopters to pick up the supplies from the drop zone and ferry them back up to the Hill. On one occasion it fell to me to supervise the loading of the nets used for the underslung loads. My pilot informed me that he would come down as low as possible to the undergrowth and I was to jump the last foot or so. So in my youthful exuberance I of course misjudged the height and jumped to early landing heavily (full kit, rifle and ammunition). This was much to the hilarity of the local Ibans that were assisting in gathering the dropped supplies and bringing them to the spot where our helicopter could approach safely for the net to be attached. I was to walk back up the hill with the Gurkhas and by the time I got back I was knackered. My biggest disappointment was when we unpacked our ration pack that had just arrived. Some funny bugger had dispatched us a 14 man 2 day compo box instead of 2 man 14 day. We ended up having to eat corned beef every other day of our stay. I’ve had an aversion for corned beef ever since and right up to the present day it is about the only thing I refuse to eat.

[1] (recently read in Borneo Boys that this was probably Dave Reid)

I am grateful to Stan Matthais for the following contributions

Stan served on 225 Squadron in 1965 and was due to fly on the ill-fated Whirlwind which crashed with total loss of life of the five on board. Some are wondering who the 4th person was who failed to go on that flight. It was Stan, taken off by his Chiefie a few hours before departure. He then went into town and was having a few drinks in the market square when he heard the news of the crash.

Another crash was XP398 which was recovered and brought back to base underslung from a Belevedere.

Stan’s comment: “You’re doing a great job Bill, evoking some memories, most good, some not so good for others. Not that I have the best of memory’s but that day [referring to the first crash] stands out, obviously as I was the one that got away.”

A day out to the beach at Baco. Dropped us off then picked us up in the afternoon just before the rain came down.

Additional note from Colin Cummings: XP359 was being flown by Brian Skillicorn who experienced an engine failure when flying out to a carrier. The aircraft was recovered and repaired. The crash of the other Whirlwind resulted in severe vertical crush forces; none of the five on board survived; the aircraft was never recovered.

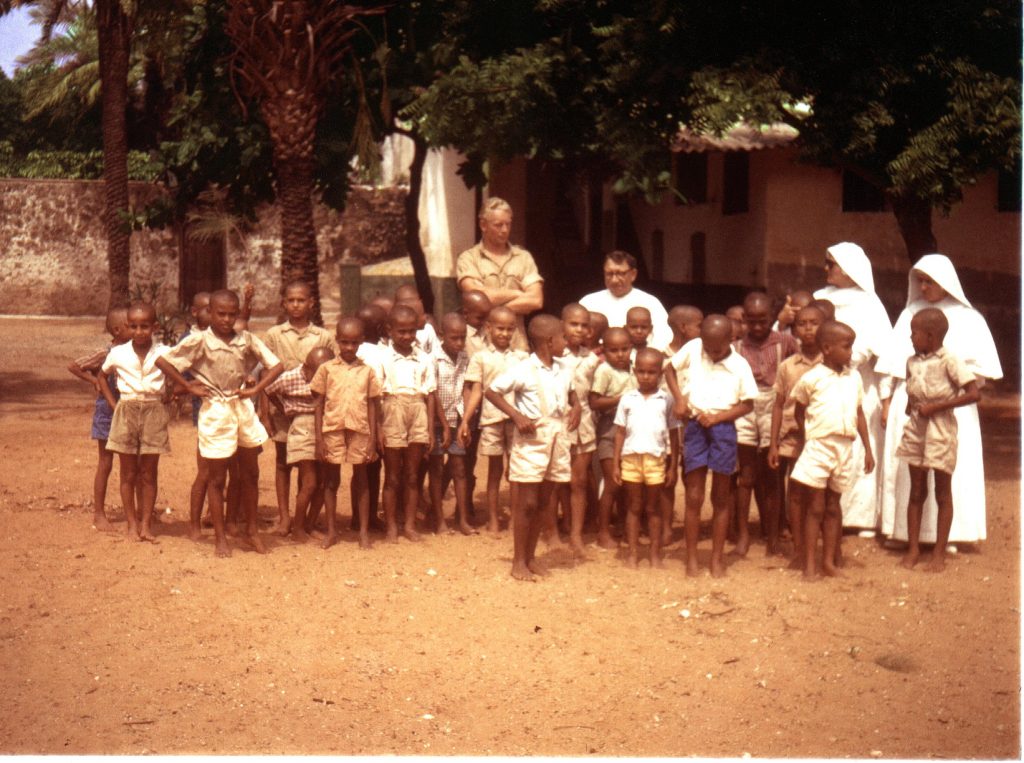

The following has been provided by Alistair Martin and is an account of the 225 Squadron operation in Kenya in 1963

Herewith some ramblings regarding the above subject. It is my belief that the squadron or part thereof was scheduled to go on exercise to north Africa, most likely to El-Adem (that I can no longer find on a Google map). However, we were diverted to Kenya to assist in a flood and famine relief situation. The Sycamores were broken down and transported by Beverleys while the personnel were flown out in Britannias.

Because RAF Eastleigh was some 5,000 feet up to start with we had to remove anything possible to reduce the all up weight because of lack of lift and this included the blister doors. Anyway, after a very few days which included flying the local District Commissioner around to survey the situation and finding suitable areas for the Beverleys to drop bags of maize for the locals, two pilots, Flt Lt Mike Ginn and myself along with 2 Sycamores were sent to Mogadishu in Somalia. A Beverley was used again to transport us.

At Mogadishu we were used to assist a World Health Organisation team to carry out surveys over an area up to some 200 miles south to places such as Merca, Baraawe, Jilib and Kismayo, taking in villages up the Juba River. As in Kenya, except here it was because of high temperatures causing reduced lift, the blister doors were removed and I recall one trip where one of the medical team was airsick while sitting in one of the canvas rear seats. He tried to direct his stomach contents out through the blister door opening but unfortunately the powerful circular air flow in from the outside had a different idea and the whole of the cockpit and those therein were plastered. The ground crew weren’t pleased any more than we were.

Somewhere, possibly at Jilib, Mike Ginn and I plus a few ground crew were temporarily camped way out in the wilds near a Roman Catholic Convent school and Leper Colony (see Photo). We were still taking out small medical teams, but my aircraft was running short of hours before a servicing. The plot was for us to take teams out but I would return and wait until Mike brought the first lot back later in the day before I also flew out to assist. Unfortunately Mike did not return so I went out in search. Luckily I soon found him quite unharmed sitting by the river near his wrecked aircraft. He was about to land, shortly after I had left him in the morning, when his tail rotor gear box came adrift and he turned some 700° before hitting the ground.

This incident brought our detachment to an end though I can no longer remember how my Sycamore returned to the UK. I do know to get back to Mogadishu I hitched a ride in a DC3 Dakota that was operated by the Ethiopian Air Force and that I stood between the pilot and co-pilot for the duration of the trip as the rear of the aircraft, without seats, was occupied by local people along with their belongings which included bedsteads and some farm animals.

This brought back many memories of my time on 225 Squadron including quite a few hours on Sycamores before you arrived Bill. Regarding the SAS escape, a slight amendment there as I loosened the canvas on the side of the lorry to enable Stan Lilley and myself to climb out. As we leopard crawled away Stan had great trouble keeping his pyjama trousers on. I had to give him my socks to partially protect his feet until, from a nearby Army Camp, we purloined some roller towelling to bind them with and an overcoat for warmth plus a beer each from the Officers mess bar. The coat was returned and the beers paid for at a later date. The long walk to camp then commenced.

Dear Alistair – It was a delight to hear from you after all these years. I regret to say that when I left the RAF and went commercial, I lost contact with all the guys except the occasional one who also joined the same company. That SAS business was amazing. I can still remember Stan’s “stand” in the next tent as if it were yesterday! These were good times with a bunch of truly great guys even though living like Boy Scouts was a bit naff! When one sees the amazing service carried out by the helicopter crews in Iraq and Afghanistan I think we can claim to have made a little contribution to their knowhow and expertise.

Are you still in contact with any of the “225 of Foot and Mouth”? I know that Alan Brew, who joined me in BA Helicopters passed away some years ago. Many other former colleagues, not from 225, have gone. My own dear wife, Margaret, who you may remember, passed away five weeks ago following a three year long lung illness. I am 75 and felt the need to put down some history in the form of a website and it is very gratifying to have former colleagues, such as your good self, make contact. I hope we can keep in touch. If you have any contributions to the website then please feel free to send them to me. Full accreditation will be given. Kind regards Bill Ashpole

Dear Bill,

So sad to hear that Margaret has passed away. I have been alerted to the 225 web site by Alistair Martin, Allan Brew’s best man 1965. It has been interesting reading and brought back many memories of Odiham in the 1960’s I am sure my father did get frustrated at the long trip to France but I recall the weather to start with was diabolical, my mother was grateful to hear you made Le Touquet! As for the SAS story I think Allan lost his expensive watch that night.

Kind regards,

Diana

Replied privately

This has really brought back old memories. I’ve a few photo’s taken during my detachment at Simmanggang. If you are interested then drop me a mail. Have some of the party we threw when the 1st 10th Gurkhas left to be replaced by the 1st New Zealand infantry.

Hi Dennis

Delighted to hear from you. Yes please – I would be very interested in your photos but do feel free to add text and I will include it all in my website with full accreditation to your good self.

Best regards

William Ashpole

Dear William

Wonderful to find your site and read about your time with my father in 225 Squadron,

I remember holding the fort as a nine year old in Odiham whilst Dad was out in Borneo. My Mother must have been very relieved when my father returned home safely.

Sadly my father passed away following a long battle with Parkinsons Disease in 2002 aged 79. My Mother passed away aged 69 after 7 years struggling with Altzheimers Disease in 1996. Sadly their retirement was cut short after 10 years in Dubai to retire near to Yeovil where Dad did his Helicopter training.

Many many thanks for recording this time and especially the photos.

kind regards

Keith Barlow ( John Barlow’s 3rd son ) Dad had 5 sons and a daughter

Dear Keith, It was such a pleasure to hear from you but I was greatly saddened to learn that both your father and your mother have passed away. Your father and I were great buddies throughout my time on 225. We got on very well together even though there was a fairly significant age difference. He wrote me a note after I left the RAF and after my time with Bristow Helicopters. He was wondering whether there might be a non-flying job for him with BEAH at Gatwick. unfortunately, the small size of the operation there was not conducive to taking on another employee. I lost contact after that and have often wondered where he was. I have the fondest memories of him as we kidded each other. I remember your mother also as a gentle lady. I am so pleased that you found the site and enjoyed the photos, one of which, showing your father, has only recently been added courtesy of Alistair Martin. Please contact me again should you wish to discuss your father further. I will then send you my personal email and telephone number. Sincerely, Bill Ashpole

Don Brims was one of our Flight Commanders, 103 Squadron, RAF Saletar, 1963-65.

Many thanks for the memories.